An Interpretive Guide to Neuralink’s Press Event

About ten minutes after the last mic was turned off, a thought occurred to me: Neuralink is going to become the Apple of internal wearables.

What follows unpacks that thought a bit, in context of a larger explainer about Neuralink’s strategy and what to take away (and not take away) from yesterday’s event.

This article was written to be accessible. We’ll explain things as we go.

As always, I reward corrections.

The Event

Some number of you might be asking: what exactly is Neuralink?

While the longform answer that Tim Urban gave on his Wait But Why blog three years ago is brilliant and canonical, it was also 38,000 words. So here’s a skinny version:

A brain-machine interface (BMI) is a piece of hardware that gets implanted inside the skull to engage the brain in some way (some call them BCIs, swapping in “computer” for “machine”). A popular example is the cochlear implant, which gives/restores hearing. One estimate from an ex DARPA employee who handled BMI funding is that ~200,000 people have some kind of implant today.

Neuralink, an Elon Musk company, just announced a BMI implant they call a “Link”, which is essentially a brain modem. It’s a small device, about the size of four stacked US quarters, that replaces a chunk of skull, from which 1,024 electrodes dangle down 3-4mm into the top region of the brain via threads 1/20th the diameter of a human hair. Each Link (which can “read-write” electrical signals) processes data using an on-board chip, shares a compressed output via Bluetooth, and recharges wirelessly using a magic wand of sorts.

What a Link does is where things get tricky. By way of analogy, what does an internet modem do? You might say it “translates” signals between systems. But what we mostly care about is what that translation allows for. In the case of a Link, that’s a very open question. Neuralink listed a dozen potential applications (from reversing blindness to dampening extreme pain), all of which boiled down to “restoring/regulating functions that aren’t working as they should”. But the full range of theoretical possibilities is as broad as “whatever is possible via fast, high-definition data transmission to and from targeted sections of the brain”.

For now though, what matters is the translation itself. A good modem translates large amounts of information accurately and quickly, thus reducing the bandwidth bottleneck between systems each otherwise capable of nearly incomprehensible data transfer speeds. And it happens that the Link just blew the doors off as far as being the best modem on the market.

As for that existing market...

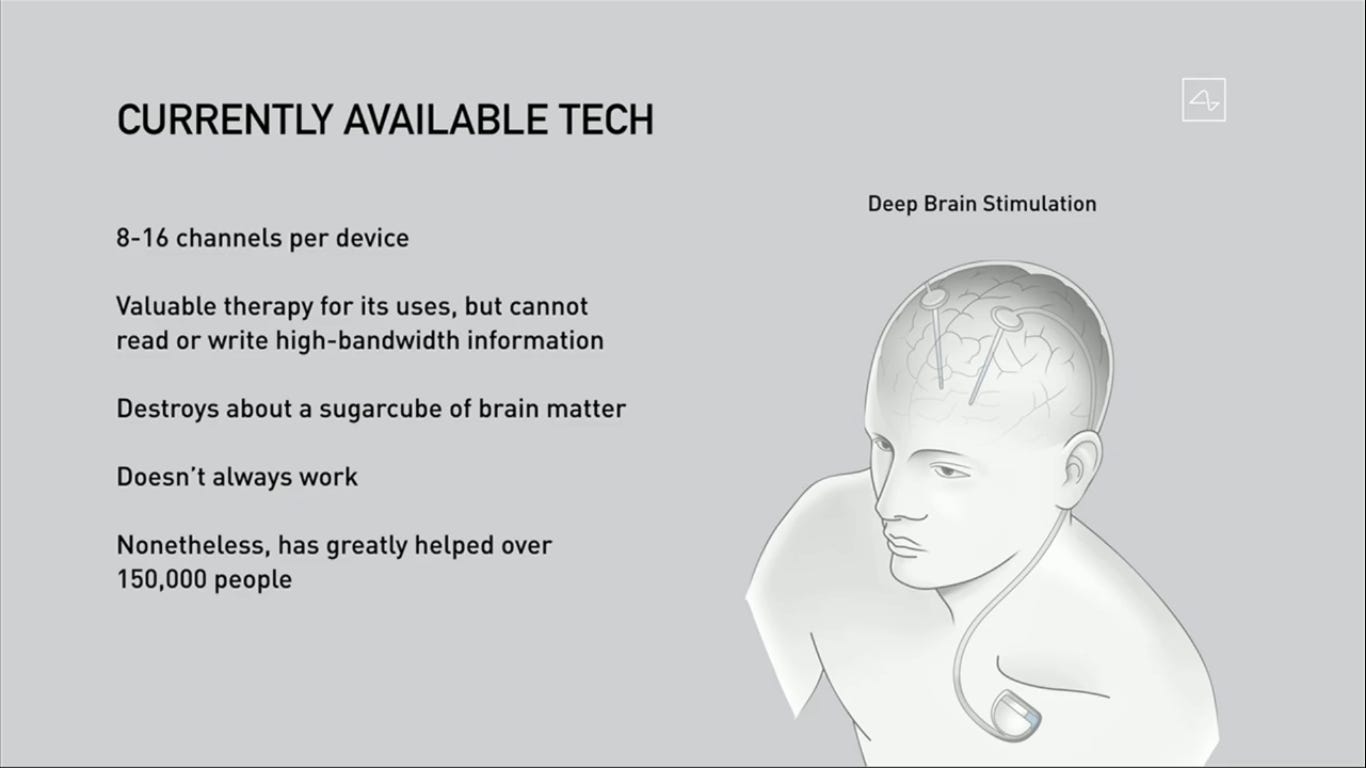

(Images taken from Neuralink’s presentation. While both Elon and his team have praised the Utah Array for the innovation it represented/unlocked, Elon had previously pointed out that it looks a bit like “a medieval torture device”, and he is not wrong. It’s like a tiny bed of really sharp nails.)

Anyway, yesterday’s event was mostly to unveil the Link (an upgrade on their prior BMI model, the N1). Weirdly though, Elon wasn’t super explicit (compared to prior comments) about why these design innovations are so important.

To give the sense quickly, let’s start with a tweet he sent out a few hours before the event:

This isn’t just some cute framing. Engineering and science have a bidirectional relationship. All technology is predicated on science, and all science is the clarification of data produced by technology. And more often than not, engineering progress is throttling the other (by happening too slowly and at an insufficient scale).

We can model it like this: data -> analysis -> explanation -> technology -> data. That is, increasing the data is what makes the science possible. So if we want to understand the brain better, we need more data. A lot of it. And that in turn both requires better brain modems and a lot more of said modems actually in human heads. They won’t guarantee any specific form of progress. But they will make it easier / more likely.

Cue Neuralink, who just announced a soon-coming future where you’ll be able to get a Link installed in about an hour via a simple/safe robot-performed outpatient surgery that won’t even involve general anaesthesia, for a cost of a few thousand US dollars.

Elon is thus (once again) focused here on commercializing the technology that solves the progress bottleneck — as good entrepreneurs should be.

The Corporate Strategy

This brings us to the “Apple for internal wearables” bit (where I’m being generous with that word by including things like replacement limbs, which I suppose are technically neither internal nor external).

To be clear, no one at Neuralink said anything yesterday about devices beyond the Link (except for a theoretical “neural shunt” that would bypass/replace non-functional parts of a damaged spine). But you can see the inevitability here. Neuralink of 2020 is a hyper-focused company of 100 working on the cornerstone device. But they’re posed to 10-100x over the next decade, and any large enough vertical integrator is going to make their own companion devices that synergize well with the “CPU” of their wizard hat.

Signalling just such a future, Neuralink was clear yesterday that they’re going to own their entire stack (including on-board chips and the surgery robot). This means better costs, better security, better interoperability, and an awful lot of growth opportunity protected by a pretty massive moat.

(Elon compared the Link to “a Fitbit in your skull”. He could just as easily have said the Apple Watch, in that both “write” data to bodies using haptic feedback. If you squint hard enough, that’s a good analogue to what the Link’s electrodes are doing.)

To make this explicit from a strategy standpoint:

The US alone has over 5 million people with various forms of limb/extremity paralysis (everything from stroke aftereffects to full quadriplegia).

The motor cortex is the part of the brain we’ve already mapped most successfully, with past BMI implants having given patients the ability to do things like move cursors and type by just thinking.

A greatly improved modem with an automated surgical insertion procedure at a commercialized price point would theoretically make this technology both more efficient and more accessible to those with paralysis.

In the course of helping this market, Neuralink expects to also unlock data collection at an unparalleled rate (which again won’t guarantee other breakthroughs, but will certainly increase the odds / lessen the difficulty).

This revenue stream would give Neuralink the resources it needs to develop whatever synergistic products it wants, thus increasing their potential user pool.

It’s a classic flywheel. Solve a really hard problem in a way that helps a niche (but not overly small) initial user base, then leverage that work towards larger ends.

Anyway, here’s what the Neuralink surgery bot looks like. It’s very Westworld, in the best way.

FAQ / Objections

I wrote this half of the newsletter in advance as a test of sorts. My strong suspicion was/is that many tech journalists would miss the point in largely predictable ways, especially on Twitter. So I designed a scorecard, where judging the utility of a given take can be done by looking at whether it focused on the incidental vs. the important on these four dimensions:

Marketing rhetoric vs. big picture motivations

Benchmarks/specs vs. progress dynamics

Timeline realism vs. timeline strategy

Risks vs. risk tradeoffs

We’ll quickly take each of those things in order.

Big Picture Motivations

Let’s zoom out to 10,000 feet.

While Elon has gotten some deserved flak over the years for in-the-moment choices, his long-term actions tend to track his guiding beliefs and the strategies that rationally follow, five of which are relevant here.

Judging from past interviews, he sincerely believes:

That humans are clever enough to build advanced AI, and foolish enough to do so carelessly

That the power and growth of advanced AI will compound via BMI implants

That bad actors working faster than good actors would be an existential risk

That accelerating the pace of BMI development is likely to unlock/create enormous human good

That most orgs suck at innovation/commercialization in ways he can control for within his own companies

Of course, one might disagree with one or more of those beliefs. The relevant fields are near consensus on some, and not so close on others. But it’s a bit silly to evaluate the rightness or wrongness of a given strategy decision divorced from its animating belief. Given the right priors, certain actions wouldn’t only make sense, they’d be moral imperatives. Hence the importance of adjudicating the beliefs themselves.

Now, I don’t mean to take a position on any of the first three here. My point is simply to suggest that Elon really does believe all five (though for 1 and 2 he’d likely assign a probability range). Thus if one is going to criticize Neuralink’s strategy, they would do well to trace the decision back to the corresponding belief and litigate that first. It’s certainly possible that a given critic has a better view of the data as to the probability of those things being true. But making robust cases in that vein is not what most of the criticism I’ve seen has looked like — which is a missed opportunity.

Progress Dynamics

There are three forms of progress that matter for BMI implants:

Getting really good at reading out data

Getting really good at analyzing that data

Getting really good at sending in data (ie., stimulating neurons)

Advances will come somewhat in the order, in that progress in one unlocks progress in the next.

As we’ve covered above, the Link is a massive improvement on comparatively primitive modems like the Utah Array. While 1,024 is a low number of channels/electrodes compared to what future iterations will have, it’s still some 10x the status quo. And the pace of innovation here could be faster than we think.

(Hardware here may follow something like Moore’s Law. Or it may not. Either way, software likely won’t. And while you might think they need far more sophisticated tools to meet certain ambitions, we won’t know until we know. It often takes roughly the same knowledge to know how far off a bit of progress is as it does to get there. And all we know today is Neuralink’s rate of innovation to the field —which is exceptional.)

Anyway, Max Hodak (Neuralink’s president) suggested one interesting benchmark: a quadriplegic person playing Starcraft with just their mind (though I suppose there could be a race there between that and actually granting limb function to said person). As to the size of the gap between today’s devices and one that would allow either of those outcomes, I think we do well to embrace some humble agnosticism. We’ll know when we know, and we don’t need to know to consider the current plan a good one.

Anyway, on a related note…

Timeline Strategy

A common Elon criticism is that he misses more timeline predictions that he makes. This has led to lots of mockery — which I’d argue is to miss the point of the timelines.

We have notoriously dim views of what’s possible right up until someone changes the status quo. Real physical and social limits exist, sure. And we’ve pressed up against them in some fields. But we haven’t come close in others. And we haven’t in most of the relevant fields here.

Nike is obsessed with the two-hour marathon. But they won't have failed if no one ever gets there (within conventional rules). Their goal is precisely difficult enough to only be possible if all involved stretch to their utmost. Good goals are like that, especially for urgent things. As it concerns Elon’s companies, what matters is how many of those goals did get accomplished, and how important the results were. To say one happened a month or a year “late” is to miss the point: a less ambitious goal would have led to a lesser result. And for projects where delays come at real human costs, that matters.

One of Neuralink’s employees said to me yesterday that “we wake up obsessed about getting a deeply useful device to those in need.”

I take that comment at face value. These goals aren’t fanciful or some marketing ploy. They’re a set of bought-into cultural expectations by which employees are measured — not exclusively in whether they hit them, but in what their attempts look like. And, sure, there are balancing considerations. Not everyone functions well at full pace. Everyone needs some balance. But Elon, despite whatever other faults, has a record of getting his teams to produce results that no competitor comes all that close to, generally on work of deep human importance. Maybe x will happen by y. Maybe it won’t. Hyper-focusing on dates is somewhat immaterial to the point of the exercise.

Risk Tradeoffs

Neuralink didn’t give an update yesterday on their timeline for human trials (the latest word from Elon, back in May, was “less than a year”; which, per the above, I understand as an internal target more than a statement of objective fact). But they did announce yesterday that they received a breakthrough device designation from the FDA in July. So human trials are coming, at whatever pace the FDA blesses.

Of course, as we’ve already seen, many will suggest that risks of human trials are high and that Neuralink should proceed slowly. While those concerns certainly shouldn't be dismissed, they should be weighed in light of three things:

Elon’s belief that he has the best people in the industry and that he’s removed innovation obstacles they’d face elsewhere (which, looking at his other companies, is hardly a crazy notion). Much of that innovation will be directed to making the device safer (for reasons both ethical and strategic) at a pace that will likely render some external criticisms outdated on fairly fast cycles.

Our biases often cause us to weigh harms in a short-sighted way. Autonomous vehicles have crashed, sure. Sometimes fatally. But most governments have come to the sensible realization that shutting down the industry until risks can be brought to some arbitrary distance from zero would lead to far, far more aggregate deaths. No amount of non-human trials will reduce the risks here to zero. But degrees matter. And tradeoffs matter. And human agency matters. Some prospective patients will understand the risks and wish strongly to take part. There should be checks and processes there, absolutely. But the ethical calculus here is unique, and excessive caution definitionally isn’t a virtue.

Going slow theoretically gives bad actors a chance to go faster. While there is disagreement about risk probability here, most agree that we don’t want the least ethical parties forcing us to play catch-up — especially considering how cognitive advantages might compound if and when this industry reaches an efficacy tipping point.

All said, there is a strong argument for moving forward carefully, but less of one for slowness outright, and many arguments against.

P.S.

While the event had been announced as a means of communicating recent progress, Elon was also explicit about it being a recruiting ad — i.e., sharing progress as a means of exciting people into applying. (They stressed that they don’t care if applicants know much about neuroscience. They’re just looking for smart people who know how to build and ship exceptional products.) Now, I’m not being paid to say any of this, but I think what they’re doing is pretty cool and important. If you agree and happen to have the skills described, you can apply here.