This story is about a particular piece of reporting. One that may not seem very important on its surface. But it’s ultimately a story about the systems that balance our incentives and fence in our worst impulses — or, rather, what happens in the absence of those systems. How do our watchers act when no one is watching over them?

While no one could say that journalists have been under-criticized of late, much of that criticism is rooted in journalism’s curious ambivalence when it comes to accountability structures. Many newspapers once had professional watchers of sorts. Most don’t now, by choice. This role has been, in their framing, ceded to us. But how to wield that delegated power well is unclear. What ought we to do when journalists break faith? To whom should we direct our concerns? Who plays judge? And what outcomes should we strive for?

In telling this story I’m betting on three things:

That enough readers will care more about truth than team, thus ensuring that the story gets heard

That some media folks will give this a fair look and really sit with the implications, thus ensuring that the story actually accomplishes something

That I’ll be speedily called to account for any errors in my telling, thus ensuring that the story doesn’t mislead

That last one is a literal financial bet by the way. Everything I publish is subject to both correction and kindness policies. If anything I’ve said here is untrue or unfair, I’ll happily compensate both the messenger and whomever I might have done wrong by.

Of course, the cost of that thoroughness is length. As such, this post contains two versions of the story: a summary intro (the entire saga in nine bullet points), followed by a much more detailed writeup with a fleshed out section for each bullet.

If you just want the gist, the summary should give the sense well enough. For those looking for a closer view of the evidence, the longer sections can be read together or individually.

__________________________

The Skinny Version

Note: I strongly recommend reading the longer versions of at least sections 5 and 9 (those about doxxing and harassment), as both involve sensitivities that can’t be easily reduced to a single paragraph. But for the sake of being clear up front: all doxxing and harassment should be soundly condemned. It’s just that the specifics here are important.

In chronological order (with my primary concerns being numbers 1, 7, and 8, where the rest just give context and completeness):

The Verge wrote a negative story back in December about tech CEO Steph Korey and the culture she’d established at her startup Away. While the piece had substance, there’s some dispute as to whether it established the right points of context to justify its publication. (Many CEOs make bad leadership decisions. We do not generally consider all sins as worthy of public exposés, just given the significant repercussions involved. Many in tech felt, not for the first time, that this particular piece didn’t ask the right questions to allow such a distinction.)

Last week Korey posted an uncharitable theory on her Instagram as to why female founders get disproportionately targeted by journalists (a real phenomenon, separate from whether Korey’s theory was either fully correct or relevant to her own case).

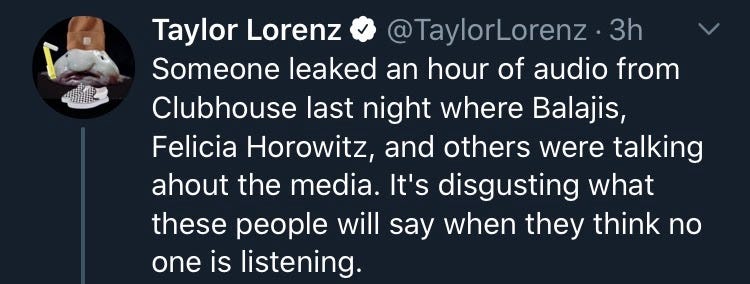

NYT reporter Taylor Lorenz took exception to said posts and wrote a mean tweet about Korey.

Silicon Valley personality Balaji Srinivasan took exception on Korey’s behalf and posted his own mean tweet that directly parodied Taylor’s language.

Taylor, in turn, complained that Balaji had been attacking her for months despite her multiple attempts at mediation (he denies both claims, and she has yet to substantiate either). As part of her complaint she shared an edited screencap of Balaji’s tweet with its context stripped. While the cropping was apparently done by someone else, the effect was prejudicial.

Later that same night they both joined a group call on the invite-only app Clubhouse. Soon after Balaji joined, Taylor left. A female participant later suggested that Taylor may have felt unsafe with Balaji’s presence (a claim Taylor herself somewhat disputed later, suggesting that she just wanted to put a lid on further attacks). A few participants then discussed both whether Taylor’s exit was justified and the appropriateness of questioning said decision. When it was Balaji’s turn to speak, he added: “Is Taylor afraid of a brown man on the street? Then she shouldn’t be afraid of a brown man in Clubhouse. I’ve literally done nothing other than one previous tweet.” Taylor then tweeted about Balaji “apparently … implying that I’m racist” while not responding to his dispute of her primary charge (which may not have been relayed to her at the time). But more than a week later now, we still have precisely the same amount of evidence supporting her main accusation as we do his racism charge.

The following day, Motherboard (a VICE imprint) published a leaked recording of an hour-long section of the Clubhouse call, which they framed in deeply misleading ways — divorcing multiple quotes from their context and otherwise maligning the participants as a collective whole (most of whom were people of color having an exceedingly civil conversation). VICE also failed to note that approximately half of the speaking time was taken up by current or former journalists/editors. (In the interest of diligence, I listened to the call several times, in addition to chatting with several participants as a sanity check.)

Many prominent journalists (including Taylor) subsequently commented on VICE’s piece with takes that I find similarly impossible to reconcile with the actual contents of the call — the effect of which was to drag both the Clubhouse community and the app’s leadership for allowing/enabling toxicity and harassment despite the call not being at all as described. In doing this, said journalists proved the original complaints: that it isn’t always about the evidence, and that tech figures often do have limited recourse when their names and work are defamed.

As an epilogue to the above, Balaji offered up a public bounty for “the best meme on this episode” (as well as the best legal analysis of the call recording/leak). Some feel the former was tantamount to incitement, especially in context of Taylor (one of several predictable subjects of the memes) being a woman. Others feel that what Taylor and VICE did was worse/first and no less likely to lead to further attacks against women, else that gender shouldn’t be considered a valid defense for an instigator anyway. And some just thought the memes were harmless in general. (My interest in said section, as really everywhere here, is to establish what happened, not to tell the reader how to feel about what happened. I have my takes, which I share. But I am not impartial.)

All said, my sense is that we have a number of journalists acting in ways they wouldn’t dare to if their institutions took the idea of accountability seriously, else if we had any healthy recourse options that they might sincerely engage with.

My sense is also that we won’t make much progress until we agree on what happened here. Hence the thoroughness of what follows. While some may find cause to say their own mean things about this piece (or about me for writing it), one point of offering bounties is establishing an accountability mechanism. If/where I’m wrong or unfair, I’m happy to make good. And I’m not even asking for the journalists to match me. Only to be mindful of the offer.

Basically, I don’t consider this to be an ambiguous story. I believe that many of these journalists are clearly and wildly in the wrong, and that this ought to matter. That others might be in the wrong too (readers can judge) is a separate question that we can and should litigate in parallel. But journalism has a unique place in our information ecosystem, and the last few years should be sufficient incentive for us to get around to seriously examining those broken dynamics. While this story might not seem enormously consequential in itself, it has the benefit of being clear in showing certain behaviors for what they are. That is, this is the sort of low-hanging case that we can either act upon or ignore.

I hope we act, and that we do so with boldness, precision, and great thoughtfulness.

__________________________

Interlude

A few more things to establish before we get into the weeds:

Most of my clients in recent years have been in tech. Plus I’m just finishing up a book on modern journalism. Plus I have my own personal history on the receiving end of what I consider (really) bad reporting. So I’m not neutral. Hence the bounties for fairness/accuracy as a check on my biases.

I’m open-minded about adjudication as it concerns those bounties. Those who don’t feel comfortable having me judge (or feel that I have failed to take their concerns in good faith) are welcome to suggest a neutral party.

I’ve censored out some names in what follows. This is because I want to give people the freedom to delete bad tweets, because I want to focus on dynamics more than individuals, and because it limits the likelihood of harassment.

However you feel about this story, please do not attack anyone involved. It won’t help any noble cause, and it will expose you as part of the problem. We all fuck up. Even where those fuckups are willful and serious, our aim should be restoration. (Extending that logic, I have no interest in cancelling anyone.)

Points 1-5 are a close adaptation of something I wrote on Quora last week. If you’ve already read that piece, you can safely skip those sections. Though there is more/better detail here.

I’m publishing this using a new Substack. If you’d like to follow, it’s $5 a month. For the next two months I’ll be donating 100% of revenues (pro-rated for annual) to the Thurgood Marshall College Fund. For any who like the content enough to stick around past that, the money will fund more pieces like this. (Some will be book chapter previews. I’ve spent some two years now pulling together a catalog of stories that are clear, immaculately sourced, and very hard to explain away. Most are about more obviously important cases, and many will be much shorter.)

Oh, and as for the name of this Substack: it’s a Community reference, but also a tongue-in-cheek response to a mean tweet a journalist once lobbed in my direction.

Game on.

__________________________

Full Story

#0: Some Background Context

To the degree that Silicon Valley can be fairly described as a whole, they’ve been in a forever feud with journalism that has gotten particularly heated this year.

The rough shape of the dispute is that many in SV believe that tech coverage is heavily slanted by:

The fact that anti-tech headlines are especially good for traffic and subscriptions

The fact that the average age/experience of reporters has gone down (buyouts of seasoned contracts, shift to web-first, etc.) at the same time that editorial input has dropped on a per-piece basis

The fact that journalists are under increasing pressure to publish the bulk of their content under clickshare dynamics (where to take longer to get a piece right/better may mean missing the main attention window)

The fact that tech now intermediates if/how journalists reach their audiences (leading to obvious frictions)

The fact that none of the major newspapers have public editors anymore (thus no one whose direct job it is to take appeals seriously)

(Whether these are indeed facts is often assumed more than shown. Even so, they represent what many in SV believe to be true, which is their frame of reference here. I’ll get into these claims more in my book, as others have elsewhere. Many obviously disagree.)

While this feud has had many flashpoints, there have been two especially notable ones these past few months, both of which have involved Balaji:

The question of how the media portrayed Silicon Valley’s COVID alarmism (and just the media’s early coverage of COVID in general). You can get the flavor here, here, here, and here. The thrust is that major outlets published many, many bad takes. (Objectors are welcome to compare this Vox piece with this screencap and this current version, the last of which has one correction note despite deep revisions. Also consider this, ahem, acknowledgement of their tweet deletion.)

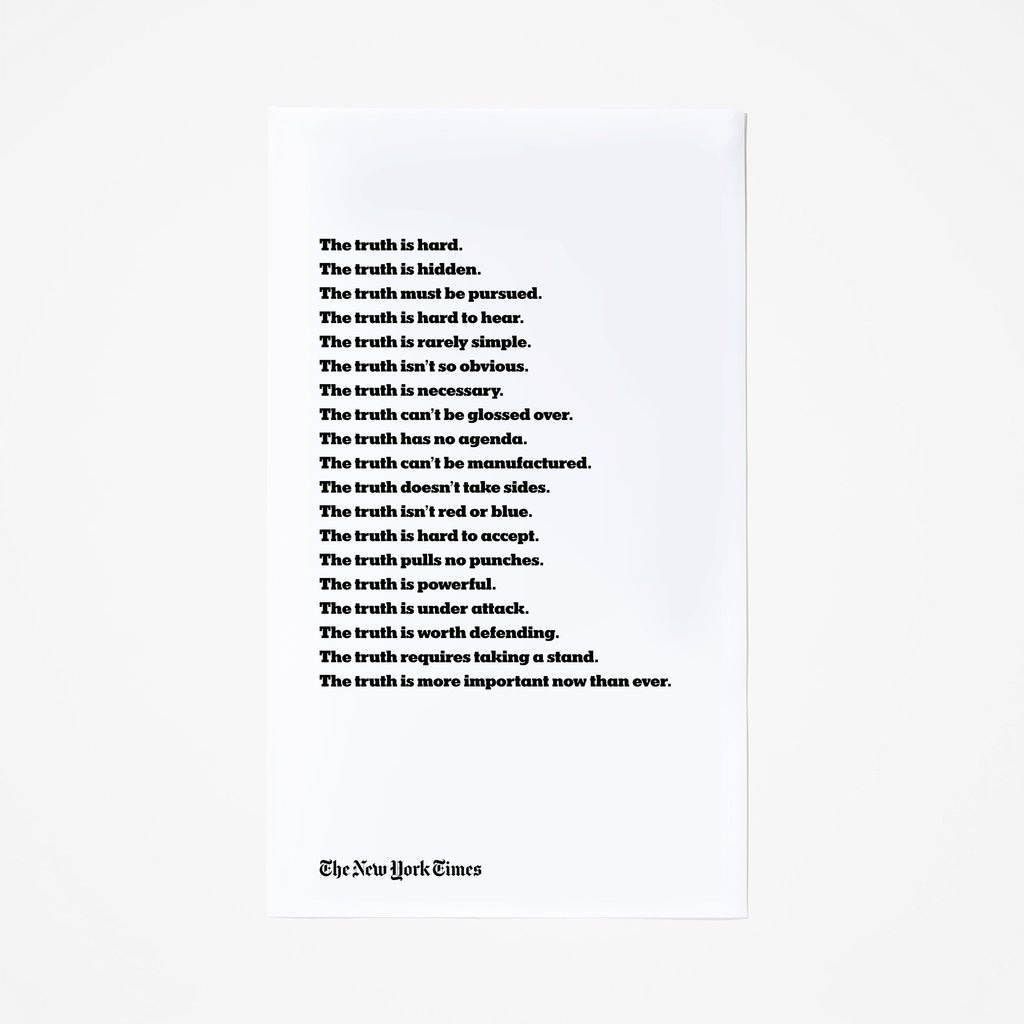

The NYT’s plan to publish the full name of Slate Star Codex’s Scott Alexander against his reasoned pleas/objections. (Scott is a favorite writer of many SV folks, most of whom saw this as doxxing without a legitimate purpose — as here).

A good part of my social network is in tech, and my subjective read was that both issues were back-breakers to many. Lots cancelled their NYT subscriptions, else made overtures to that end. And major tech figures like Ben Horowitz, Naval Ravikant, Jason Calacanis, and Justin Kan all retweeted the #ghostnyt hashtag and/or advised their portfolio companies against speaking to journalists. While it wasn’t the first time that something like this had happened, it did feel like quite an escalation tonally.

Anyway, this gives us a backdrop for the particular case of reporting that ultimately led to the current dustup.

__________________________

#1: The Verge v. Steph Korey

The Verge (who, for disclosure purposes, I am rather biased against given what I consider to be their past defamation against me) published this back in December:

Emotional baggage: inside the toxic work environment at Away

Away’s founders sold a vision of travel and inclusion, but former employees say it masked a toxic work environment.

Away is a travel-focused tech startup (mostly luggage right now). The gist of The Verge’s narrative was that co-founder / then-CEO Steph Korey had been pushing employees beyond what was reasonable and had otherwise been something of a bully.

Of course, it’s impossible for many in tech circles to read a story like this neutrally. For illustrative purposes, you can imagine two very different takes:

VCs / Tech CEOs: “Look, startups are stress boilers. People who take jobs there know this and sign up accordingly, and are generally compensated in a way that gives them long-term upside that makes the pain worth it. And, sure, many founders are prickly. While it’s often the same quality that makes them good on other dimensions, the downsides aren’t always well managed and in some cases can be severe. But we believe the answer there is coaching, better supervision, and/or occasional firings based on concerns brought to board members and sponsoring VCs and so on.”

General Readers: “Wow, that place sounds terrible! The CEO is taking advantage of frontline workers and otherwise being very abusive. I’m glad that someone told this story. Bad leaders and companies need to be held to account in exactly this sort of way.”

I’m personally a little torn. What was described/disclosed in said article certainly looked pretty bad. But it was hard to tell exactly how bad without more context.

To give a few examples:

We’re told that employees were repeatedly (to some point in time prior to and unrelated to the reporting) coerced into working unpaid overtime. But we aren’t told how often this happened (only the rough duration of two such seasons). Startup employees regularly work long hours at various inflection points in a startup’s growth (or in response to various fuckups along the way). Away had enough velocity to simply hire more staffers, which makes one wonder why they didn’t just do this earlier if being behind was a chronic occurrence. My sense is that more rounded journalism would have asked this question to give a sense of whether/how Away was a true outlier to industry norms.

There was sparse discussion of compensation (just a salary figure for one junior employee in 2017 when Away had a headcount of ~50 and had just closed their Series A round). Were the employees mostly getting stock options? (I’ve heard yes, but through a source that wasn’t 100% sure.) If they weren’t, the treatment is worse. If they were, it’s something of an employee choice. Do they want to stay in a ruthless job until their options vest or not? In quite bad conditions, some might very reasonably choose no, and might find just cause to leave a castigating review on Glassdoor on their way out. And others might choose to both stay and escalate their concerns up the ladder. So it goes. Some leaders are bad, and we have controls for this outside of the extraordinary step of leaking to journalists. But this article doesn’t really help us understand the employees’s decision map, nor which other interventions were attempted prior. (We know about some internal complaints. We know nothing about which investors or board members were approached, or how.)

Six employees were fired in May 2018, purportedly for their comments in a Slack channel intended for venting by LGBTQ+/PoC employees. The article captures a dispute about which words were used in the firing, but doesn’t relay what the actual fireable comments were (only that Korey was apparently tight-mouthed about them, and that two comments highlighted to the fired employees included the phrase “cis white men”). It’s possible that Korey was being vindictive towards employees who were just expressing their grievances in some raw way (which would obviously be very bad!). But it’s also possible that the comments were simply beyond the pale (even for venting) and that the firings were justified. Given that the reporter was willing to post screencaps of things that Korey had said in various Slack channels, why didn’t we get an anonymized taste of what had set her off based on the clues she had? (I’m not assuming that these were left out maliciously. But it’s a bad imbalance that should have been caught by the reporter and/or her editors.)

These are not trivial concerns. And it’s the routine absence of these kinds of clarifying details that has fed into SV’s perception of tech reporters as not always entirely motivated by virtuous motives (so much as a blend of noble impulses, not-so-noble impulses, and bad editorial incentives/controls — with the latter being predicated on more or less broken revenue models).

And it’s not like the downstream consequences of this sort of reporting are unknown at this point. Negative media coverage directly affects a company’s brand equity (sometimes profoundly so), making it harder for them to attract recruits, raise capital, and secure fair future coverage. While those can be just penalties for wrongdoing in cases of serious misdeeds, the foreseeable costs ought to warrant great thoughtfulness in how and when that sledgehammer is wielded — especially given how these costs fall on employees (who are often partially, and sometimes primarily, compensated in equity).

Anyway, Korey stepped down as CEO (into a chairwoman role) right after the Verge’s piece came out, accelerating a long-planned move. Then, a few weeks later, she reversed course and said she would be returning as co-CEO for a while. (In the wake of this recent drama, Away affirmed that Korey would be relinquishing her co-CEO role at some point after her return from maternity leave later this year. But this was also mischaracterized by some. It wasn’t a new move. Hence the phrasing “original timeline” in the quoted memo. That said, there’s apparently been a new employee push to oust her, this time also predicated on a culturally insensitive Pocahontas Halloween costume.)

Point is though, what all the VCs and tech leaders I’ve spoken to claim to want isn’t freedom from censure. Most want to know when someone they’re invested in becomes a liability (though they’d obviously prefer to find out privately). Their main objection is to the lack of controls around these stories. If there were a series of objective tests that a draft had to meet, my strong guess is that many of those concerns would go away (thus allowing some of those remaining to be more fairly labelled as bad faith). But these controls don’t exist in any universal sense, nor does it seem that most outlets have any such system (or at least they haven’t made them public, thus defeating the point). So far as I can tell, it’s mostly just whatever editors feel is newsworthy by some personal calculus, which is, uh, not a great check for a tool of that weight.

__________________________

#2: Steph Korey v. The Media

Korey made a series of posts on Instagram Stories last week, including this three-parter (screencaps are Taylor’s):

It’s important to separate two things here:

Assuming that Korey’s comments were informed by her own situation (very likely), did the dynamics she’s describing have much to do with her actual case?

How accurate is her theory of modern media dynamics in general?

The first one is difficult. I’m inclined to believe that what was happening at Away did merit some form of intervention. And if those employees did indeed try the normal routes of redress to no avail, I’d hardly fault them for reaching out to a friendly reporter. And having reached such a point, that reporter (and her editors) then had the choice of whether/how the subject’s gender should influence their reporting (which is a rhyming question to whether/how public criticisms against female journalists should be softened because of the subject’s gender). How the folks at The Verge weighed this is unclear. Even so, they published the story. Now, were they primarily motivated by expected piece performance? I doubt it. I suspect the team genuinely believed that they were standing up for workers in need (where the traffic was just a bonus). But to the degree that Korey believes that the original writeup was insufficiently justified (not unreasonable), I can appreciate why she may see it otherwise. Ergo, if she were to write some defensive posts about it on her Instagram, I’d be inclined to let her be, even where some of her commentary might be questionable. To the degree that the original reporting was sound, it would always be the best response.

The second case is easier. While we’ll cover some specific defenses proposed by various journalists in later sections, it’s worth noting one big thing here: clicks (i.e, traffic) are how all publishers make money. Whether this money comes from ads or subscriptions only changes so much. In the latter case, signups are a product of eyeballs x conversion rate. Even if the latter is really high (roughly-but-not-always indicating strong quality), you need traffic. Hence the powerful incentive of “let’s optimize at least some pieces for traffic”. The best publishers find some reasonable balance here. Most don’t. And no one does this well all the time. (For a particularly egregious example of the NYT chasing traffic at the expense of discernible journalistic standards, see here.) Basically, there are virtuous ways of chasing traffic, and there are less virtuous ways. I think most critics agree that the best outlets get this right a lot of the time. The problem is the quantity of incidents where they don’t (and the lack of means of redress when this happens). And obviously some lesser outlets just don’t care about balance at all.

(I’m still of two minds on the easier-defamation-suits front. While I’m a strong believer in protections for good faith journalism, the problem here is arbitrary journalism that isn’t meaningfully held to any fixed standards. And so I’m a bit sympathetic to those who’ve been victimized by journalistic overreach. As mentioned, I count myself as having been on the receiving end of that, and the NYT elected not to answer my request to work with them to publish my own response. I was annoyed. Not enough to sue anyone. But I could see why someone would. Again, this feels like a problem that can be solved on journalism’s side by installing controls / means of appeal. If this is done reasonably, it becomes easier to identify insincere complaints. But in the absence of such systems I get why some who feel victimized might wish for stronger ways of hitting back.)

Anyway, I can see how a journalist might look at Korey’s posts and get a little fired up. Her comments represent a strong set of charges against one’s co-workers. If I’m a reporter, I’m likely to feel defensive on the grounds of intent. That is, I might think “look, my friends and I work hard to write good stories, and while the system in which we work might have certain bents, our individual motivations are purer than all that”. While I don’t think this is a particularly sophisticated way of looking at it (“no raindrop believes itself responsible for the flood”), I certainly get the impulse.

__________________________

#3: Taylor vs. Korey

While only Taylor could say whether / to what degree her specific motivations were premised on what I outlined above, her shot at Korey was pretty harsh:

Meanness aside, let’s recall the distinction between the coherence of Korey’s theory and its relevance to Korey’s specific case. Taylor attacks the first explicitly here, in rather strong language.

Bear in mind that many in tech reading this:

Already felt that many journalists weren’t taking concerns about unbalanced incentives / absent controls / broken dynamics all that seriously.

Already felt on Korey’s side as it concerned the roundedness of The Verge’s reporting (even if some also felt that Korey was not entirely innocent).

From this point of view, you can imagine how someone in tech might react to Taylor’s tweet using a similar mental model to how a journalist was likely to react to Korey’s (i.e., on the level of defending one’s team from what one perceives as uncharitable / overstated attacks).

And that’s exactly what happened.

__________________________

#4: Balaji v. Taylor, Round One

Given the context outlined in section 0, we have to remember that Balaji was already pretty deep into a general feud with journalism (with Balaji having fairly strong standing going into this given the wild imbalance as it concerned COVID coverage).

Anyway, he replied in kind:

Note the language: it’s a direct parody of what Taylor wrote about Korey (with an emoji at the end just for emphasis).

Now, is this a mean thing to do? Sure! Though, per the reasons outlined in prior sections, it’s difficult for me to perceive the difference between its meanness and that which Taylor showed towards Korey.

That said, one could argue:

That it isn’t reasonable for a third party to be aggressive on someone else’s behalf.

That it isn’t morally right to do so when you’re a man (especially a man of some influence) and the counter-party is a woman (just given the asymmetrical harassment that women receive in general).

(From the opposite position, we should also consider race. The western press’s coverage of non-white men is, how shall we say, not a historic point of pride. And the resulting stereotypes have introduced real harms for Black and Indian men, especially in relation to certain accusations. While this hardly negates the gender asymmetry, we can consider both lenses without reducing the other.)

Anyway, the first argument isn’t compelling to me. That’s how lots of bluechecks use Twitter (even if they shouldn’t). And it’s exactly what Taylor did in her clapback to Korey (who hadn’t said anything about Taylor specifically that I’m aware of).

The second consideration gives me more pause. It’s 2020. We should all know by now how asymmetrical harassment is, and we should all be allies in the cause of making the internet a safer place for women (as well as LGBTQ+/colored voices). That said, this begets an obvious moral hazard. If we (as male voices) all agree to soften our public criticisms against women because of that asymmetry, what happens if/when an woman with a large platform uses this cover to attack someone? Should we cede counter-criticism to female voices exclusively? Or, if we do opt to wade in, should we consciously dial back our tone compared to that of the aggressor? As a white man, I like both options (the first more, with the second as an occasional fallback). But others (including many women I’ve spoken to) disagree on the grounds of equality / emotional labor, and I will never ascribe misogynistic impulses to said stances unless there is clear evidence of misogyny otherwise.

Anyway, Balaji did what he did.

__________________________

#5: Balaji v. Taylor, Round Two

And then we have Taylor’s response:

A few things here:

This is not a retweet. Taylor pasted in a screencap of Balaji’s tweet, which she says she received from someone else (as he’d blocked her by then). While I don’t question the truth of that claim, there’s still the obvious problem that doing it this way strips out context. Not that his parody wasn’t mean in itself. But that’s a very different sort of mean from writing a tweet like that ex nihilo. And if anyone is experienced enough with social media dynamics to understand how this move would play out, it would be the reporter best known for writing on how people use social products (which, incidentally, I think she’s done a great job of).

Taylor makes a strong set of accusations here. It isn’t just that she finds this specific tweet mean. Her concern is the total effect of his prior bashing (“constantly trying to destroy my career on the internet and in private”; “one of many, many vicious tweets he’s posted about me”). Thing is though: she has yet to substantiate this claim. Working under the assumption that she was telling the truth, I was curious to see what he’d said about her. I was able to find exactly two tweets (a back-to-back pair) from his account that either tagged her handle or mentioned her first or last names, only one of which I see as offensive (in some mild sense). And she had only mentioned his name in one tweet prior to July 1st (a response to the aforementioned dig). Now, this obviously doesn’t prove his innocence. He could have subtweeted her, deleted other tweets some time ago, and/or attacked her on other platforms or offline. But he’s made strong denials here, and Taylor has so far furnished no evidence or further explanation. I asked her for her side both via PM (see bottom here) and via public comment, and received no reply, other than that she blocked me three days later for reasons unknown — which is a decision I support her right to make regardless of cause. (As for cause, all are welcome to read my messages to her / browse my Twitter activity and tell me if they find anything objectionable. I don’t see it anywhere. But that could be exactly the problem!)

If Taylor does release evidence for her claims (which would definitely change the story), there’s still the question of whether it’s fair to level that kind of accusation without any serious attempt at substantiating it (whether to the public or some trusted third party) either at the time or in the week following. While we should certainly support all women as if we believed them when they speak out about harassment, this is not to say that we ought to treat the accused as guilty by accusation alone. And where those two presumptions of innocence remain in tension, it’s on some court to decide (again, private or public, as sensitivities and preferences dictate). But if one party opts to not submit any evidence to an adjudicator, it’s far from obvious to me why we should break the tie in their favor. We have historically rejected such approaches to justice for excellent and uncontroversial reasons.

Taylor also claims to have made no fewer than two attempts to get Balaji to back off. When I asked him, he said he was only aware of a single attempt, which came via a mutual contact after his late June 30th “disgraceful current journalist” tweet and just prior to Taylor’s “he declined my call once again” July 1st response (emphasis mine). Balaji says he took the intermediary’s call and gave them a message to pass back. And his understanding is that this person did so. Again, he very well could have lied to me! But I would suggest, in light of his strong denials, that the onus is on Taylor to prove a point that could be trivially proven.

(Note: I consulted what I believe to be a complete archive of the 17 tweets that Balaji has deleted over the past three months. Most were typo fixes that were subsequently reposted, mostly within a few minutes. None were more than an hour old when deleted. None mentioned Taylor. As anyone has cause to question this, I’m happy to share my findings with a neutral/trusted party.)

Anyway, more tweets and other drama followed, which we’ll get to in later sections. The main point here is that this story looks very different based on whether we believe: (a) that Balaji doesn’t have a history of attacking Taylor and was simply clapping back on Korey’s behalf in what he felt was equal measure, or (b) that Balaji does have such a history, and that his tweet should thus be viewed in that context.

It isn’t that the first scenario would absolve all criticism. But the two are very different scenarios, and so far we have no evidence supporting the latter interpretation.

__________________________

#6: Clubhouse v. Taylor

Taylor left the group call shortly after Balaji joined. Exactly two of the dozen or so speakers voiced a negative opinion on her exit:

Felicia Horowitz (a prominent Silicon Valley figure who often hosts/moderates calls on Clubhouse and has a small ownership stake in the app) expressed frustration (starting at 12:21 on the recording) at the implication that anyone had cause to feel unsafe in an environment that she, a Black woman, has presumably made no small effort to make/keep safe. She thus questioned (at 14:34) Taylor’s willingness to have the conversation on Twitter if safety was the real concern. As to the Twitter feud itself, Felicia suggested (at 34:37) that “you can’t fucking hit somebody, attack them, and just say ‘hey, I have ovaries and therefore you can’t clap back.’” While that was a rather crude way of putting it, the question of validity there is again predicated on our stance on the proportionality between what Taylor tweeted about Korey (and later Balaji) vs. what Balaji tweeted about Taylor. Because if those actions were roughly equal (and if Balaji has no prior history of attacking Taylor), what exactly is the objection there if not gender dynamics? (Again, I’m not assuming the truth of any of these propositions. Readers should weigh for themselves based on the evidence. My point is just modelling what Felicia’s view likely was based on the data points available at the time.)

Balaji, starting at 20:25: “Is Taylor afraid of a brown man on the street? Then she shouldn’t be afraid of a brown man in Clubhouse. I’ve literally done nothing other than one previous tweet. … The whole talking about [me] tweeting [about Taylor] as harassment [is] completely illegitimate, completely wrong, completely fabricated, and just false.” While I think the racial framing here was unwarranted (Balaji disagrees), I also think we ought to judge in context of what followed (i.e., his anger at being, to his testimony, falsely accused of serious wrongdoing). While one wouldn’t quite excuse the other, it would certainly mitigate it to some degree. And again, this is very different if he’s been dishonest with me about their history. But if he has been honest, he gets to choose which motive(s) he ascribes her thus-false accusations to. While racism is obviously a strong choice, said speculation follows the accusations in sequence. Hence the importance of establishing whether said accusations are indeed true before we litigate the framing. And given that no one has as of yet found/announced supporting evidence from Balaji’s Twitter history (or elsewhere), the onus is reasonably on Taylor to substantiate her claims. If/as she is able to do so, then we can/should prosecute this too.

Otherwise, four other participants spoke up on Taylor’s behalf (11:23-12:21, 12:34-13:09, 14:19-15:22, 33:50-34:35), and no one said anything bash-y. The next closest we get is Roland Martin, a career journalist, suggesting (26:23-32:53) that he felt Taylor’s tweet about Korey crossed the reporting-editorial line, for which he thought she needed to “accept responsibility”. (He also added that if one does take an editorial “swing at someone”, the swinger can’t reasonably object to a response in kind — though he was careful to distinguish between return criticism and harassment.)

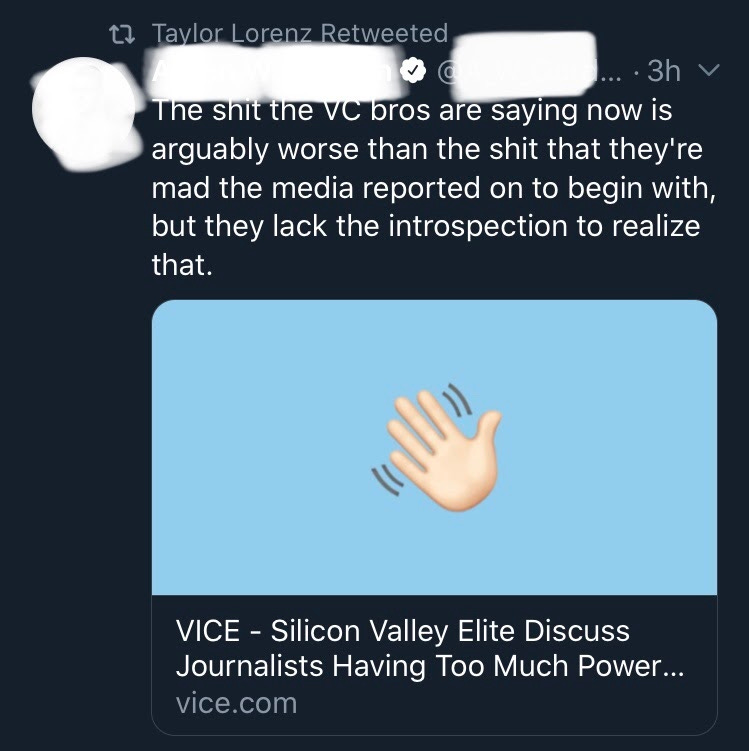

But if we compare Roland’s comments to VICE’s take of participants “suggesting that Lorenz had crossed a line on Twitter and must be punished” (emphasis mine), this is where have to start asking whether they didn’t listen to the call, didn’t comprehend it, or just decided to lie about what it said. Because there is a gulf between emphasizing the importance of responsibility/accountability and suggesting that someone should be punished. And no one on the recording ever suggested the latter.

Anyway, it happens that Taylor retweeted said VICE snippet:

I’ll leave it to the reader to judge what exactly is “terrifying” about the call, or just how we’re supposed to accept any of this narration as reliable. While it’s possible that Taylor simply hadn’t yet listened to the call when she tweeted the above, my personal judgment is that this would hardly excuse a lack of retraction later once she had.

I should also note that others ran with this same “punished” line, leading me to offer a $100 bounty if anyone can give me a timestamp that might fit the bill. (I am, uh, not expecting to have to pay this one out.)

__________________________

#7: VICE v. Clubhouse

My original plan was to review their article paragraph by paragraph. But this piece is already too long, so what follows are highlights (lowlights?) that give the sense:

VICE’s headline: “Silicon Valley Elite Discuss Journalists Having Too Much Power in Private App”. Subheadline: “In leaked audio from an invite-only app, venture capitalists pondered everything they think is wrong with journalists.” A few things about these descriptions: (i) many sections of the call were about power v. responsibility (25:57, 31:07, 37:27, 44:35, etc), which is quite a different thing from “too much power”; (ii) if my annotations are correct, slightly over half (29:54 / 59:26) of the speaking time on the call was taken up by two journalists and a former senior editor at WIRED; (iii) consider the difference between “wrong with journalists” and “wrong with journalism”.

VICE refers to Roland Martin as a “television personality”. Wikipedia, meanwhile, calls him a journalist. Texas A&M, which granted him his journalism degree, put him in their Hall of Honor for his work as a journalist. The National Association of Black Journalists named him their Journalist of the Year in 2013. If you get the theme here, ask yourself why VICE went with a different label. Also ask why they didn’t mention that he was by far the most vocal person on that call (taking up 17:43 / 30% or so).

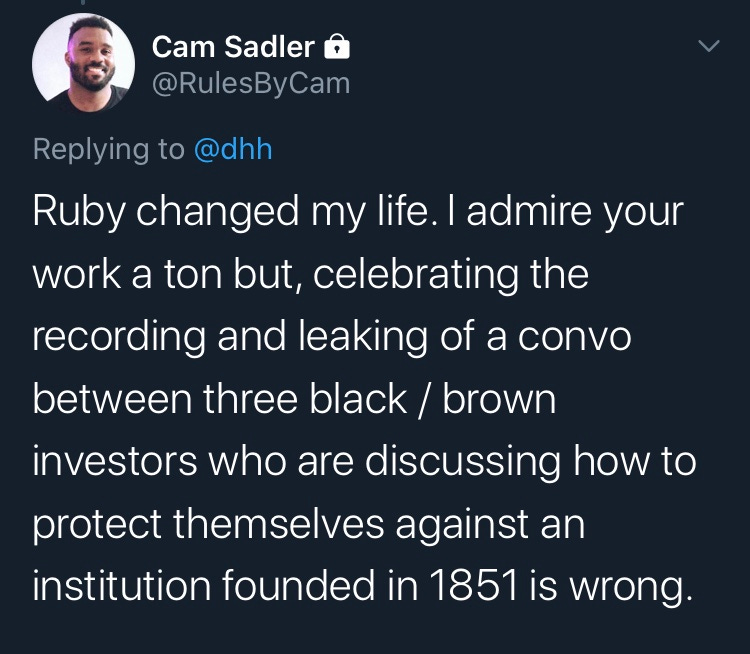

Compare VICE’s presentation of one of Nait Jones’s comments (starts with “[w]hen it comes to our industry”) with what he actually said on the call (9:38-11:20). It’s, uh, a pretty stark difference yeah? (By the way, Nait is a Black man with an incredible story, who is doing important work on improving inclusion in tech.)

VICE quotes an NYT piece (written by Taylor) about Clubhouse to explain the app. But note the paragraph that begins “[s]ometimes there is a tarot card reader” and compare it to Taylor’s original. The establishing sentence has been omitted. Consider why, and what the effect of that omission is.

Quoting VICE: “After [Taylor] left, the participants began discussing whether [she] was playing ‘the woman card’ when speaking out about her harassment.” Well, no. Exactly one participant raised such a point (as to their motivations, see section #6).

Quoting VICE: “The audio chat had spiraled wildly out of control…” The epitome of this apparent mayhem? Balaji talking (20:25-24:32) about tech press complicity in “covering up the threat of COVID-19” and otherwise articulating his belief that media corporations are “disaligned” with their citizenries. Ok? Well, one can dispute the language of “covering up” (which Balaji qualifies at 22:45). But the media did widely downplay the threat of COVID, did mock people in tech for sounding early alarms, and didn’t meaningfully recant or apologize (see the many links in section #0). And as for misalignment, Balaji’s contention is that revenue dynamics are at some odds with the civic functions of journalism. This is hardly a fringe position! Edward R. Murrow was talking about this back in 1958 (beginning at “I am frightened by the imbalance…”). And anyway, Balaji was the only one on the call proposing anything that anyone might term radical. And he spoke for about seven minutes out of sixty.

Quoting VICE: “The conversation essentially resembled a Gamergate chat…” Uh, what? Gamergate involved the active coordination of nasty and prolonged harassment against a number of women. The Clubhouse call was mostly just nice people (more or less evenly split by gender; nearly all non-white) discussing the great Spider-Man challenge of balancing power and responsibility. To equate the two events is some mix of disingenuous and delusional. Balaji and Felicia each made a comment that I can see reasonable minds finding objectionable (see prior section). But Felicia was adamant about Clubhouse being a safe space (see user testimonials at end of the next section), and Balaji’s one comment about harassment was a defensive challenge regarding the truth of Taylor’s claim. There were otherwise zero pro-mob or anti-Taylor comments (beyond soft chiding by the journalists on the call re: Taylor’s having, in their judgment, wrongly crossed into editorial, where their proposed solution was a colleague and/or editor bringing it up with her). So I have no idea where VICE is seeing either harassment or the type of incitement likely to lead that way.

VICE, in trying to downplay the whole “NYT threatening to publish Scott Alexander’s full name” narrative said “[i]t is worth noting that Alexander has republished SlateStarCodex blogs in books using his full name.” As tech reporters ought to appreciate, his primary objection clearly isn’t some internet detective being able to solve the (repeatedly solved) mystery of his surname. The problem is the NYT’s reach, plus their prodigious SEO. If that article got published, not only might a patient or two see it, but any patient that searched his name thereafter would be likely to see said story near the top of their results.

Consider the journalistic function of words like “exhausting” and “tedious” in how VICE employs them.

The legality of covertly recording and leaking part of the call is an open question. That said, I’m personally more interested in other ethical lenses: (i) would journalists have sung a different tune if this was done to them?; (ii) by which standards (if any) was the content of that call judged to be newsworthy enough to justify the privacy violations in publishing it?; (iii) did the journalists involved consider the well-known problems of context collapse?; (iv) did the journalists involved consider that group calls allow for revision and synthesis and emotional resolution in ways that selective leaking works directly against?

VICE says “the idea that fishing for ‘clicks’ to drive ad revenue is a successful or even common business model is a fallacy”. But as I outlined above (and as Paul Graham pointed out here), the distinction between clicks-for-ads and clicks-for-conversions is not especially meaningful for our purposes (they just produce different kinds of clickbait, where the former is a general impulse purchase and the latter more a form of tribal affirmation). All publishers chase traffic and optimize accordingly (if sometimes unconsciously and often through ambient norms), even where they also do some amount of carefully-establishing-the-truth reporting where traffic is wholly secondary. Sure, many are moving away from ad revenue. So what? Who is moving in the direction of writing stories with greater care or stronger editorial controls? Most are just swapping one hook for another (else not even bothering with that). But don’t take my word for it. See takes from media figures here, here, and here.

All said, VICE’s story was turned around in about half a day. Despite the manpower thrown at it (five credited people!), what they came up with was exceptionally poor journalism reflective of the larger thesis here. And its excesses incurred real and undeserved costs to several people of color (one of whom felt compelled to nuke his Twitter in the aftermath).

(1851 being the NYT’s founding. Also, Cam is not the one who left Twitter. That was a Black investor who was directly defamed by VICE. Lastly, Cam is replying to the “bunch of VCs plotting how to punish a journalist” guy, not a reporter.)

__________________________

#8: Team Journalism v. Clubhouse

What follows is a sampling of retweets of the VICE story covered in the prior section.

(I’ve redacted identifiers here for the anti-harassment reasons listed at the beginning. But all are from professional media people with verified accounts and no fewer than 10k followers.)

(This dig comes at the expense of a Black VC whose quote VICE split to make it sound worse. See commentary in previous section.)

(As for “VC bros”, the number of speakers on the recording was roughly equal as far as gender went, and nearly all were people of color.)

(I agree with the “everyone should listen” part!)

(Besides the fact that no fewer than three current/past journalists/editors were on the call and spoke for approximately half of it, Balaji actually suggested inviting another one on at 2:04. Plus, Taylor, who professionally reports on social media platforms, got an invite. So…)

(While agreeing with the top half here, no one said the bottom bit. The only person on the call to express a familiarity with Taylor’s work praised it. See 32:53-34:45.)

(Clubhouse certainly has some rich and powerful users. Perhaps a few who are legitimately globally so. But those who spoke on the call were largely not. And the article was about those on that one call.)

(I’m starting to think that invoking Gamergate is like Godwin’s Law for tech reporters.)

(Of course no one was on the record! That’s, you know, definitionally what happens on a surreptitiously-recorded call! And as for being willing to identify oneself to VICE, why would anyone want to do that for an article like this?)

(Hilariously, that one was written by a bureau chief for a media outlet funded by, you guessed it, VC money.)

(Right, Gawker was destroyed because it dared to criticize tech people. Not because it outed a gay man who then famously took revenge by funding a massive and successful lawsuit against them for invading someone else’s privacy in a particularly gross way.)

(To the degree that it’s true for either, consider which fits the “vicious hatred” bill more: that top tweet, or the call itself. Also consider the tweets that follow.)

In contrast, we have commentary from those who actually use the app:

For more like that, see here. My impression from talking to users over the past week (several of whom were on the call in question) is that Clubhouse has taken an intentional approach to seeding the app with nice / interesting people, taking special care to ensure strong user diversity. Indeed, the only negative takes I’ve encountered have been from (i) journalists who haven’t used it, and (ii) journalists who couldn’t give a faithful account of the single hour of audio made available to them.

__________________________

#9: Team Balaji v. Team Journalism

Well, Balaji decided to have some fun with all this:

Taylor’s take:

As for the memes, I leave it to the reader to judge. Per the structure of the challenge, none of the selected ones were narrow to Taylor herself (though many do mention her). Are they flattering? No. But memes rarely are. They’re reductive caricatures, just by definition. And the parties being caricatured rarely find this process nice or fair. And while I don’t question that some memes can cross into harassment territory, I don’t personally find that any of the selected ones come all that close (though it’s certainly possible that others were created that were worse, and that I just didn’t see them). That said, I also don’t doubt that Taylor has been attacked during this episode (as have others), or that the bounties (even though not specific to her) led to some downstream piling on by less restrained individuals. Some will fault Balaji for this. (I think they were a bad idea, personally.) But however you rule on that, I’m not sure how it’s materially different than all those gross journalist tweets about Clubhouse and its users (which I think were much worse content-wise). Said journalists gleefully propagated a (non-visual) meme that was deeply prejudicial against a group they believed deserving of their mockery. And said party included several women (Felicia Horowitz, plus all the other female speakers who got broad-brushed), along with a number of people of color, at least one of whom quit Twitter because of it. (A white VC also reported being doxxed in the aftermath; interview about it here). Is this better because the mean words didn’t come with GIFs from 300 or Happy Gilmore?

Anyway, in talking to my group chat about mean memes, one of them created this. So this is my gift to any journalists feeling down right now.

(To be clear, I am not wearing a garbage bag. It’s a beard bib, and it is an amazing invention. But, granted, I otherwise do look like a hasn’t-showered-yet quarantine trash panda in search of meth. So it goes. I wanted to see what would happened if I shaved around and left a mustache, and, well, now we know.)

I also stumbled upon this one:

It’s not about me (that I know of). But it is eerily similar to the comments I got from many professional journalists during this episode. Point is, people on the internet can be mean and/or unfair, regardless of their profession.

May we choose to be better.

Jeremy doesn't like to self endorse much, but you might also enjoy this piece by him on immigration in which he repudiates the bad faith backlash against Trudeau: https://www.quora.com/Does-Justin-Trudeau-deserve-the-criticism-hes-getting-from-conservatives-for-his-stance-on-refugees-and-irregular-migrants/answer/Jeremy-Arnold-4?ch=10&share=a7346633&srid=urmn