Israel-Palestine, Community Notes, Oil

On how moral clarity depends on informational clarity, on how X can provide more of it, and on why I may be headed to Israel. Plus a sidebar on strategic oil reserves.

Preface: Life comes at you fast. After I drafted the below last night, I fired it off to a few friends for review and closed my laptop for dinner. Before we’d even finished eating we got an alert advising us to book flights to safety ASAP. The root cause of the local escalation? Not just what happened in Gaza, but how it was initially reported by journalists and governments across the world. While I’ve worked in a small bit of commentary here about all that (in bolded brackets), the rather sad thing is that I didn’t really need to add anything to what I originally wrote to make the same case. That something like this would happen was inevitable—just as it will be the next time, and the next, until we finally take the problem seriously.

Israel-Palestine

I.

I’ve been travelling with a Jewish-Israeli friend. We were less than a day away from arriving in Ashdod—some 25 miles north of Gaza—when we heard the news.

We eventually took a phone break to take an evening walk around Port Said. I asked her if she’d have felt safe doing the same walk without me. She said no.

The next morning we learned that two Israeli tourists had been shot by police in Alexandria, where we’d been just the day prior. And Egypt isn’t a particularly unsafe place. But identity can change that—even if only so far as replacing the natural wonder of exploration with an unnatural need for vigilance.

For the last week we’ve been in a different Muslim-majority country as we try to navigate whether it’s safe for her to return to her kibbutz, whether she even wants to, and where she/we might be able to fly from. Our second day here was the called-for Global Day of Jihad. We wondered what would that mean for her. Probably nothing? We’ve been treated very well here, and most Muslims are for peace. But it only takes a few, and these things do happen. How safe would you feel as a Jew? More to the point: where exactly would you feel safe?

It turns out there was a rally just down the street from where we had dinner. She likely wouldn’t have been in danger if we’d walked through. She’s not wearing a Star of David on her neck. But we were suddenly mindful of things that didn’t matter before. What if she took her father’s call in a cab and answered in Hebrew? What if someone at a cafe saw her typing on her phone? Would it matter that she might have been texting her Palestinian friend as she continued to try to hold her world as one?

My heart has always hurt for Palestine. It still does. A tragedy is a tragedy, however one assigns the blame. I was moved by the poverty I saw in the West Bank when I visited last year. I ended up buying some expensive (though excellent) craftworks that I had no use for as a nomad, just to throw a few bucks into an economy so desperately in need. As we crossed the border I kicked myself that I hadn’t bought more.

At the bottom of it all though, the world needs a place where Jews can feel safe. There’s no solution that doesn’t accommodate that truth. That we’re further away from that now than we were a week ago is yet another tragedy—especially given that we aren’t any closer to peace and prosperity for Palestinians either.

II.

I’ve been asking a lot of friends—many Jewish, many not—their thoughts on the conflict. Most don’t know quite what to think, recognizing their own lack of expertise. Few feel they can pick a side (or even state where they support and don’t support each side) without better info. So their open speech only happens in safe group chats, and public spheres get taken over by those with more confidence. Some of the latter have the confidence that comes with real insight. And some, well, you know.

In the next section we’ll get into how Community Notes can do more here, in a way that no other social platform has seriously tried. But to set context here’s a few questions I want you to ask yourself:

Did Israel give Gazans just 24 hours to vacate the north in their first warning? If not, how long? Who issued this warning? When? To whom?

Did Israel bomb Gaza’s border with Egypt? If so, what specifically was bombed and what impact did this have on a potential evacuation corridor?

What does Gaza have in terms of independent water and electricity supplies? Why don’t they have more? How much harm was caused by the recent cuts?

Did Israel attack the transportation corridor between Gaza’s north and south as refugees were migrating? If it wasn’t them, who did?

The answers to these questions matter. Perhaps not enough to push someone entirely between sides. But enough to give one pause in which narratives they choose to endorse in public, or at least at which speed. And this has a real effect in the aggregate. Every take that we consume and/or endorse colors our perceptions and influences how we pull our respective levers of power. We ought to, as Viktor Frankl once implored, make better use of the space between stimulus and response.

That in mind, I ask again: precisely how sure you are you that you know the correct answers to any of the above questions? And why are you sure?

There are all kinds of larger historical debates that are much less amenable to definitive answers. Land rights, for example, can only be clarified until they reach a point that depends on a wider subjective philosophy. Even if you have, say, a firm stance on the issue of the McMahon-Hussein correspondence, that only gets you so far before you’re confronted with murkier issues of contested sovereignty and when and why military might became disfavoured as a means of settling borders.

But even in the absence of shared clarity on all questions, we can have full clarity on some, like the questions above. Each is knowable, and in many cases already known. We just haven’t found a way to get those answers broadcasted in a broadly trusted way.

(You may wonder why I didn't include answers here. Perhaps you feel unsatisfied. I hope to get to at least some of them by and by. It takes a while, at the cost of crowding out paying work. But the primary point isn’t whether you had any of them right. It’s the confidence you felt in your answers, and where that confidence came from.)

[We can obviously apply this same logic to the explosion from last night. Provisional findings from an independent Pentagon investigation are that it likely wasn’t caused by Israel. And original reports of casualties and damage are difficult to square with today’s Palestine-supplied visual evidence. Still a tragedy, no doubt. Every loss of life is, in a deep way. But embassies weren’t stormed last night because of an ambiguous and likely accidental strike to a crowded parking lot. They were stormed because people had a legitimized belief that Israel had intentionally bombed a hospital, killing 500+. And this was entirely avoidable. The story was simply “Explosion observed near hospital in Gaza. More to follow as we investigate.” Instead, many credibility-claiming outlets ran with framing sourced wholly to Hamas, without being nearly careful enough to make it clear that they had no other intel, that it would be impossible for anyone to meaningfully estimate casualties that quickly, and that Hamas is notoriously untrustworthy.]

III.

I’ve been thinking about flying into Israel.1

It’s not that I think the journalists on the ground there (or in Palestine) aren’t doing a good job. They largely are, at real cost. But I do worry that the products formed by their labor are in many cases not really helping the information war. There’s too much focus on breaking news, and not enough on the fine details of recent days. I don’t blame the individuals for that much. As ever, it’s the systems and incentives.

Consider this clip, from an unrelated financial story. The gist is that a much-followed crypto news account jumped the gun Monday on a major announcement. Their mistake was amplified and quickly became a prompt for a lot of large bets. Then it came out that, oops, they were wrong. Their Editor-in-Chief’s reply?

This is what happens when we are having constant pressure to be the first with every news. This is not a problem of journalism per se. It’s a problem of the society, and of the technology … where if you’re not the first, you’re the last.

I suppose she’s right here in a mechanical sense, if wrong in a moral sense. It’s true that demand for information is immediate, and that rewards for providing it skew towards the fastest. But it’s also true that a considerable number of people value correct information, and that a mild delay is a fine price for this. It just takes more work to cultivate a brand for doing this well. But, like, what’s the alternative?

Anyway, I obviously doubt that me going to Israel would shift the balance much. And some of what I’d like to do there I could do from a laptop anywhere. But in-person access is better, and there are stories among the affected that I think are worth hearing and amplifying. My experience in Ukraine was that reporters are largely tasked with official sources, and that this doesn’t always give those far away a fully humanized sense of impact or viewpoints.

I’ll decide over the next day or two. Reader feedback here is welcome. I have no desire to play propagandist for either side, and it feels like jumping into the fray when I have no real skin in the game is, uh, unlikely to benefit me a lot personally.

Even so, I think it’s important work. And I think the world would be better if someone did it. Who will?

Community Notes

Cribbing from an email I sent back in May:

There's a way that Community Notes could be tweaked to: (1) show all bad/rushed/slanted reporting for what it is, (2) make Twitter by far the best + most trusted "ok what actually happened" source.

Right now notes are indexed to individual tweets. This lack of centralization means most notes are never made public (too dispersed to get enough upvotes), else are only visible in disconnected silos. By indexing notes to trending stories instead (only for the most important stories), users would be able to see all upvoted notes together as a sort of wiki for that story. This would be a much, much better UX than Wikipedia or Snopes, and much, much faster.

(One other benefit I’ll add here is that abusing Community Notes is harder the more you centralize them. Most of the abuse I see today is a product of many individual notes never getting sufficient attention from those with opposing arguments.)

I’m happy to report that the Community Notes team just announced some product updates that are moving in this direction. I hope they go the rest of the way. Because this would be a uniquely helpful product. Though of course it would still be dependent on journalists—both professional and citizen—doing the hard work of finding definitive evidence that can be pointed to by these notes. But I’m reasonably hopeful there. Lots of bright and neutral people want to help with this sort of thing. They just need better tools and the right compensation model.

As this war has progressed, Twitter/X has received the expected headlines about being an information cesspool. What’s missing from most of that commentary is that no other platforms are immune to the underlying problems, and X is at least doing something good to fight for reality. Whatever your broader feelings on Musk or his management, a robust platform for fact-checking on that scale is a universal good. I hope the progress continues. And that other platforms try.

Oil

This is a less important PS, but worth mentioning just to demonstrate how much the “trust the professionals” argument only works for journalism when the professionals (1) know what they’re talking about, (2) don’t engage in cheap sensationalism. Many professional journalists really do clear both those bars! But it would be nice if the industry acknowledged just how many don’t, especially at prestigious publications.

I recently happened upon a tweet that opened with:

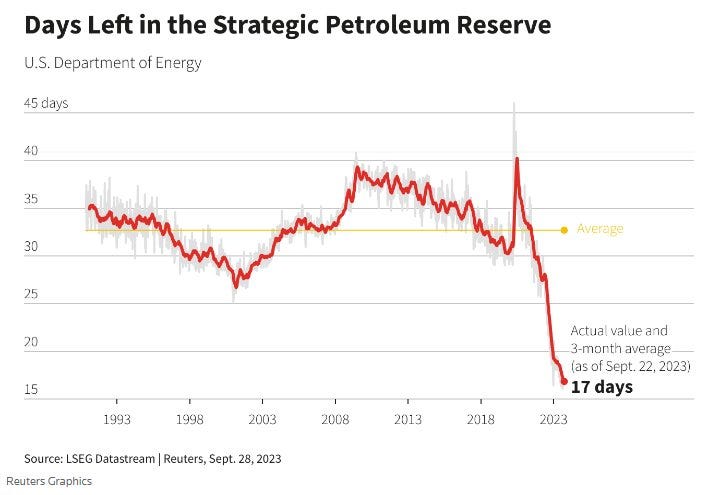

According to Reuters, the US currently has just 17 days of supply left in the Strategic Petroleum Reserves (SPR).

It included this chart:

This all seems very dire, until you understand that “17 days” is a metric that serves no real purpose other than to alarm.2

As of October 1st, 2023, the SPR held around 350m barrels of various crude types. Crucially, the four SPR sites have a combined maximum total daily withdrawal capacity of about 4.4m barrels per day. Which is to say that you couldn’t even deplete them all in 17 days if you wanted to.

More crucially, there is no such need. A much more meaningful metric is how many days the reserves could endure a worst-case supply interruption. Now, this isn’t easy to quantify, as different crude types aren’t fully interchangeable and the risk factors of new supplies being cut off varies between them (OPEC may stop sending some; Canada almost certainly won’t, plus there is extra domestic capacity for some and not others). But the Dallas Federal Reserve released a very thoughtful analysis earlier this month, the gist of which is that the SPR could survive nearly six months with zero overseas imports.3 And, as one would expect, the mix shift of the SPR’s reserves has shifted towards the crude types most vulnerable to disruption:

When considering only overseas imports that are arguably more prone to disruption than other sources, SPR inventories are roughly double their historic average, even at today’s low absolute level.

Right, so no great cause for alarm here. Or really any alarm at all. The SPR had a different function in an era when the US wasn’t a major oil source / net exporter, and before various supplies were secured from Canada and Mexico. The SPR’s main purpose now is to ensure that the US is well ahead of its minimum safety commitments for its most vulnerable imports—which it absolutely is.

The SPR can be understood like any other insurance mechanism. You can be as insured as you like, but coverage isn’t free. Being a little overinsured is good and safe and wise, but being a lot overinsured means (usually) imposing losses on taxpayers. If we’re going to argue for heavy overinsurance (ie. filling the SPR to the brim), then let’s make that argument with an acknowledgement of the price tag and not just alarmism based on a metric that can only serve to mislead the casual reader.

Of course the real moral: even when the source is a credible-seeming news org, they can still be wrong—either in facts or framing, or both.

The news needs a critical feedback loop. And to acknowledge that they need one.

Though not Palestine, no. Not that I’m uninterested in stories from all sides. But the risk factor is very different right now, and I’m skeptical that I’d be let in anyway.

In fairness to Reuters, I couldn’t find the original piece this graphic was attached to. I suspect it was some subscriber-only newsletter or some paywalled product. But even if they contextualized the number there somewhat, the graphic being labelled as it is was still needlessly alarmist given that it was designed to be shared without said context (hence being labelled and watermarked as it was).

Not entirely right, as this figure aggregates all overseas import types together. Some specific crude types would run dry faster than others. But at the least the US would have several months to gameplan a response before this happened, not <17 days.

Every story I read from you is like stepping on solid ground after walking across a river of ice shards. Thanks for what you are doing. I do not have an opinion on your trip. I really do, though, want to hear the answers to those damn questions. What is so important about those questions is that they are easy to ignore and later forget as they pop up in my thoughts while reading news of the war(s). Easy because, when forgotten, they do not upset the narrative I prefer. But they are each vital to actual understanding. I remember when I read each odd occurrence at the time and thought: "Hmmm. Why was that? Is that true? I bet there is a 'rest of that story'?" And then I quickly moved on and never thought of them again until you mentioned them all grouped together. It was jarring. This is how cognitive dissonance is so insidious.

I think it's your choice about flying. It's very dangerous of course, and do what you are comfortable with. But there is a need for responsible journalism by people who care about factualism more than factionalism.

Outsiders aren't really let into Gaza. Business as usual is happening in the West Bank, and unless the war expands there, the risk factor there may not be so different from that of Israel.

You might want to join the Israel-Palestine Spaces on Quora to share this post and anything else you have with members of the Quora community who follow the Israel-Palestine topic. Let me know and I would be delighted to invite you as a contributor to https://unityisstrength.quora.com/ and https://israelpalestinedebate.quora.com/, the main Spaces I moderate. It might get some interest in your Substack.

And of course I'd be delighted if you subscribed to our new Substack, https://unityisstrength.substack.com/