Mor and Joseph

A window into daily life for the internal refugees within Israel, and a profile of one of the many volunteers supporting them.

As preface, I want to acknowledge the obvious optical complication of writing about internal refugees within Israel. Though there are perhaps a quarter million of them now, humanitarian conditions here are certainly very different than in Gaza. While some aspects of their experiences rhyme, many don’t. Not being able to enter Gaza, I can’t capture the latter’s stories in the same way. But nothing here is meant to foreground one at the expense of the other. Both have stories deserving of being told—and sat with.

I hope both are told well.

“When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’” ― Mister Rogers

I found some helpers at one of the hotels I stayed at in Tel Aviv.

It didn’t take long in chatting with them—as was true of my experience in Ukraine, and I suppose is true of warzones everywhere—to get a sense of the sheer scale of impromptu volunteer networks that have had to materalize to fill in the gaps between local needs and the broad government programs that never quite meet them.

A trio of divorced Jewish fathers had found each other here, and committed to spending their days doing the good they could. One of them, Joseph, who’d flown in from his home in Prague a month ago, took it upon himself to check in on displaced refugees living at the hotel next door. There are roughly 100 of them on any given day, including 20-25 kids—one of them a newborn delivered here. Together they’re just a small fraction of the 250,000 or so now displaced throughout the country.

The Empty Beach

Life at these hotels is complicated, logistically and emotionally. The displaced are stuck waiting, unsure when they can return home, unsure whether they ever will return home, and unsure exactly what is left of home to return to. All manage these feelings as best they can. Understandably, tempers sometimes flare. Though mostly all share what they have and try to hold it together for their children.

Those children, as children do, mostly try to play together and find candy. They dash around the interior open-air courtyard on scooters or with a soccer ball. They sometimes pop into an adjoining storeroom that’s been turned into a makeshift play room. All surely need therapy to explore the feelings they don’t even have the language or frameworks to understand yet. Most are still on a waitlist.

While the Israeli government provided an initial stipend and covers accommodation costs, many of the refugees are unable to return to work. Families rely on donations for winter clothing, for educational supplies, for baby formula, for snacks—and for any of the other creature comforts we often take for granted.

One telling thing: despite being right across from quite a nice section of beach1, few leave the hotel complex to use it. Learning to feel safe again is never a straight line.

Mor’s Story

The 10/7 massacre started early in the morning. Alarms in Sderot—just about a mile from the Gazan border—began a little after 6am. At first it was rockets. This itself wasn’t unusual. But then came the sound of guns, followed by frantic texting.

Mor, along with her husband and three young children, went into their shelter by 6:30am or so. They wouldn’t be cleared to leave again until around 1pm the next day.

They had the TV on, in an attempt to understand the scale of the attacks and when help might arrive. As the day wore on, the announced death tolls grew. The dead in Sderot included a minibus full of 15 pensioners, some of them holocaust survivors, who were unable to get into one of the local shelters after their bus broke down.

At one point Mor’s 4.5 year old boy grew frightened that his parents—who were in the room with him—had been killed. Children’s mind are like that. They aren’t built to understand war. He now struggles to go to the bathroom alone at night. Something is wrong in his world, but he doesn’t understand what. The language that he needs to understand it all is still years away. Mor overhead him saying to someone in the courtyard, “I don’t have a home. I live in the hotel.”

In the before times, Mor worked as an architect in nearby Ashkelon—which is where the family went the day after the attack, to check in on her parents. They left with the clothes and supplies they could fit in their car. After about a week, when it became clear that the rockets weren’t going to stop, they moved on to Tel Aviv. They haven’t been able to return since. Perhaps in January the government says. Perhaps.

Life is safer here. Though not quite safe. Most rockets never get this far. But some do, and you can never be sure. Hence the gap between the children and the beach.

The kids miss their friends. They miss playing outside. Many even miss school.

Parents miss routine.

The first thing Mor said she wants to do when she gets home? Clean. Then watch movies as a family—a return to normalcy.

Going Home Again

Some of the destroyed cities and kibbutzim will be repaired, rebuilt, and reinhabited. But even the residents who do return will find that the place has changed—in some deeper sense than fresh paint and concrete. They’ll be returning to find that part of what made home home is gone. The chords once struck there in the complex music that gives a place its character will never ring in quite the same way again.

The Book of Ezra recounts a scene where the refugees from Babylon and Persia, having finally returned to Jerusalem, gathered to witness the foundation of the new temple being laid. The older refugees—who had been alive to see Solomon’s temple before its destruction—wept while the younger ones shouted for joy. One can imagine that it wasn’t that the elders didn’t share a sense of this joy—but that they also mourned for what once was, and for the music they’d never hear again.

We must hope that children—in both Israel and Gaza—will one day see the ruined places rebuilt. And that they will once again play outside without fear. And that this new music they create and experience together will be passed on to their children—even if it’s music that, to their parents, has complicated notes of both joy and loss.

Helping the Helpers

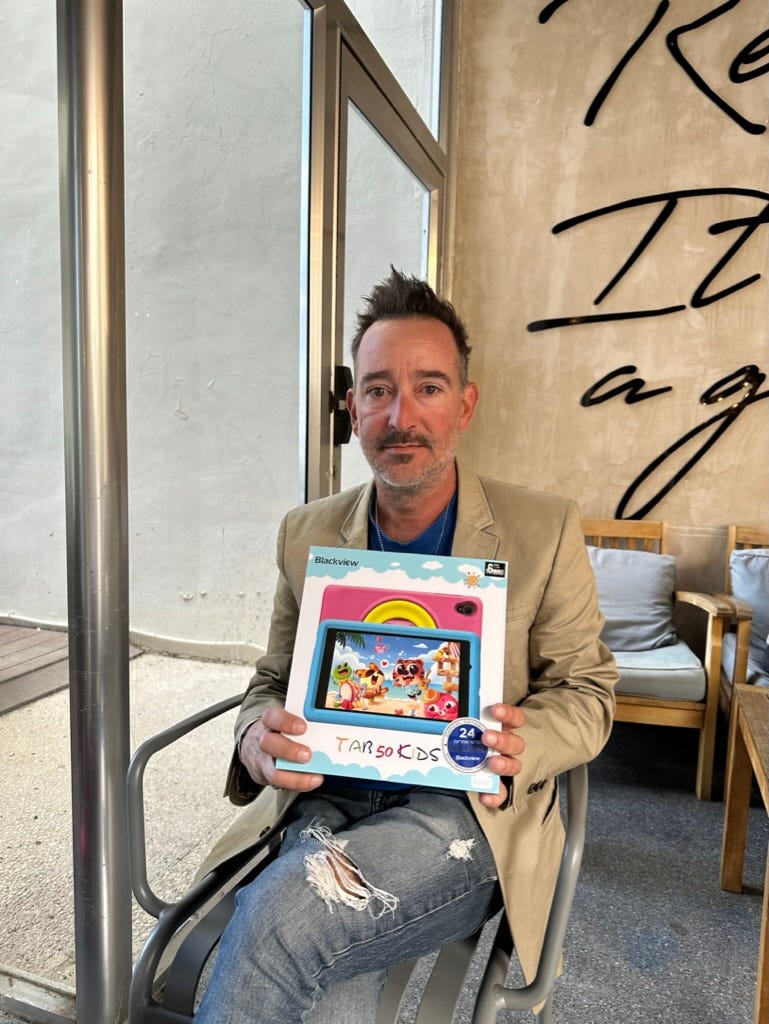

I’m going to close with a brief meditation that Joseph wrote while reflecting on one of the Shabbat concerts performed for the families most Fridays nights. If you’d like to support the work he’s doing, he can accept transfers via PayPal*. 100% will go to the families. Their top need right now is more tablets for the children—both so they can both stay current on their schoolwork and to give their parents a little extra relief.

* EDIT Dec 8th: There was an issue with Joseph’s PayPal and it seems transfers didn’t go through. As a workaround, please send to my Israeli friend here using this link. She will then transfer 100% using a local app.

Joseph has secured a deal to purchase more tablets at cost from a local dealer—with shatter-proof cases included. So far all have come from his pocket.

Impact of the Israeli-Hamas Conflict on Displaced Children: "A Song Crying for Hope” - by Joseph Rumley

Silence is sometimes more deafening than the roar of war.

We recently visited a hotel in Tel Aviv sheltering families displaced from the conflict-ridden North and South. In the midst of a crowd of parents and children, a 10-year-old vocalist filled the air with music, providing a momentary escape from the harsh realities they face. The echoes of their collective struggles continue to resonate, with musicians among them who, like the rest, couldn't return home.

As we traversed the North, we encountered haunting scenes of empty neighborhoods and deserted playgrounds—ghost towns shaped by conflict. Many soldiers had to leave behind their families, children, wives, and grandparents, clinging to the hope that home would remain a haven of safety.

Intense emotions are not exclusive to one side of the conflict; they are shared by both children and families who find themselves displaced. Leaving behind generational homes with only the clothes on their backs and meager provisions in their cars, they bear witness to scenes of devastation and horror. Amidst the chaos, a profound sense of guilt often emerges, with haunting questions like, "Why am I alive when our friends and family are not?" echoing on both sides of this conflict.

Perhaps it is in recognition of this fear and the unsettling silence that many find solace in song. The act of singing becomes more than just a form of expression; it transforms into a collective defiance against the oppressive quietude and a means to navigate the emotions that accompany life in the midst of conflict. In the face of fear, their voices become a powerful instrument, resonating with a shared determination to reclaim hope and drown out the silence that threatens to consume them.

More pieces from my reporting here will follow through December. For a preview of what I’m working on, see the first section of this post.

To be clear, the beach isn’t always empty in an absolute sense. Many locals still enjoy it. It’s more (though not only) the displaced that struggle with feeling safe. War touches people in different, complex ways. Everyone here—and in Gaza—has been affected by it. But some have a much more visceral response to eg the risk of rocket fire.