ProPublica's reporting helped get a software company sued. Was their reporting fair?

The company behind popular property management software YieldStar is facing a class-action lawsuit, at least in part thanks to ProPublica's reporting. Is this deserved?

ProPublica is a proudly activist newspaper. Their stated mission is “to expose abuses of power and betrayals of the public trust … using the moral force of investigative journalism to spur reform through the sustained spotlighting of wrongdoing.”

There’s a lot to like with this in theory! Holding power to account is a bedrock function of healthy democracy, and investigative journalism has long been the primary vehicle by which this happens. Done well, it’s essential.

But what happens when newspapers like this overstate a case? Or when they do so serially, while also refusing to reconsider their approach to reporting?1

ProPublica’s latest target is RealPage, the property management software company behind YieldStar, a product that (a) allows landlords to see aggregated market pricing data and (b) suggests algorithmic pricing decisions based on that data.

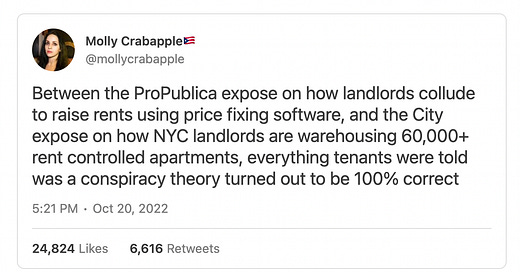

While we’ll get into the specifics, here’s a taste of the public’s reaction:

Note the specific language here: “collude”, “raise rents”, “price fixing software”, “cartel". These are extraordinary characterizations! But they’re also pretty reasonable takes if we accept ProPublica’s reporting as factual and fairly framed.

Setting aside the obvious question there for a minute, let’s note that it wasn’t just the internet that got angry. RealPage, along with several of their larger clients, is now facing litigation. Three days after ProPublica’s story dropped, a class-action lawsuit followed. While the exact relationship between these events is opaque2, ProPublica was happy to point out the non-coincidence:

Of course, this outcome are exactly what we’d expect from ProPublica living up to its mission: they shone a light at something unethical, and the public responded in kind.

But are YieldStar’s core functions actually unethical? While the software was certainly designed to approach a legal line, there’s nothing illegal—or inherently unethical, or even notably concerning—about approaching a line if you don’t cross it.

While I’ll leave it to the reader to judge whether lines have really been crossed as we unravel this story, my contention is that this case is less about clear-cut “abuses of power and betrayals of the public trust” and more just simple politics. ProPublica seems to have written their piece with ideological blinders on—leading to a predictable set of misunderstandings and leaps of logic that made them far more certain about YieldStar’s essential badness than the evidence seems to support.

We reward corrections. See something wrong, misleading, or unfair? Use our anonymous Typeform or drop a comment in this post’s dispute doc.

Bias disclosure: I’m center-left on most social issues, and center-right on most economic questions. But even with coverage where I support the journalist’s political position, it’s crucial that they’re transparent and fair. Otherwise it just hurts our cause long-term.

Price discovery vs price fixing

Before we can get into how YieldStar works—and from there how its functions relate to US antitrust law—we need to start with something far more basic. I’m sorry for how Econ 101 this is, but as we’ll see it’s really the heart of the whole case.

To disambiguate between two basic market dynamics:

Price discovery is when buyers and sellers look around at the prices of broadly similar transactions to understand the true “market price”.

Price fixing is when market participants (usually sellers) look at this data and then agree to unfairly manipulate said prices.

The second depends on the first. If you don’t know how much your competitor is charging, you can’t collude to overcharge anyone. But there’s no necessary progression from one to the other. You can increase price discovery to its maximum (ie. sellers all know exactly what others are charging) without this leading to anything unethical. Indeed, increasing price discovery is generally a great thing for consumers.

The status quo

Price discovery differs a lot by market. To use common examples, stocks and bonds are (mostly) priced in very public and comparable ways, while the market for collectibles is notoriously opaque. Not only are the latter transactions less fungible (two different pieces of art have less in common than two stock certificates), but most collectible trades leave minimal public records to work with. While occasional auctions help create some price discovery, expert valuations can range wildly.

As a rule, better price discovery is better for the system. It leads to more transactions happening at “fair” (ie. market-based) prices, and it increases public confidence that they’re not getting had. But of course whether or not it’s good for you individually depends on whether the inefficiency of low price discovery happens to benefit you.

If you own a famous pawn shop, low price discovery is incredibly helpful. Experts will say “this could be worth anywhere from $1k to $2k”, and you can then make an offer at a discount to the lower bound. While these deals are bad for sellers on aggregate, they’re often more interested in ready money than they are in visiting a dozen shops/experts for themselves to compare. So bad deals abound.

If you’re shopping for an apartment rental and you’re not in a hurry, low price discovery between sellers (ie. landlords) is good for you. You’ll end up quickly getting a good idea of fair prices, and can then shop for relative deals.

Now, of course you getting a relatively good deal on rent is net bad for the seller. You win at their expense. While you’ve done nothing wrong in shopping for the best deal, if the price was based purely on the seller having less current data (as opposed to you having, say, superlative credit history or personality etc) then you’ve definitionally exploited a market inefficiency to your benefit.

This in mind, if I gave you a magic wand and said that you could increase or decrease price discovery among landlords, which would you choose:

If you decrease it, there will be more good deals for keen shoppers. But mispricing goes both ways. Not only are good deals for you bad deals for landlords, but many units may also be mispriced too high. Just because you’re winning the trade doesn’t mean the average renter is.

If you increase it, there will be fewer good deals and fewer bad deals, as the market collapses around its natural pricing equilibrium.

Whichever way you’d personally use the wand though, two points here: (1) we’re talking about tradeoffs, (2) neither use of the wand is price fixing.

How YieldStar works

RealPage makes a software suite for property owners/managers that digitizes a lot of their normal business functions, like letting renters submit applications and pay online. The YieldStar part of the software mostly digitizes price discovery itself.

More granularly:

Property managers using at least one RealPage service have some ~20m rental units between them, mostly in the US.

Some of these managers share their rental pricing data with RealPage. (We don’t know how many, though it seems to be on a building-by-building basis.)

RealPage (via the YieldStar product) uses this data to get a precise view of what local renters are actually paying for comparable units (as opposed to what prices might be listed online, which are just negotiation starting points).

While no individual property manager can see what any other specific building is charging, they can see aggregated data for neighbourhoods.

YieldStar is also a predictive algorithm. It suggests to property mangers what they should charge to maximize overall revenues.

ProPublica seems to have five main concerns with this. In their view:

This data sharing shouldn’t be allowed, as it enables possible price fixing.

The way that YieldStar’s algorithm suggests prices is either price fixing or close enough to justify the coverage’s framing (“How a Secret3 Rent Algorithm Pushes Rents Higher”).

The algorithm occasionally recommends that property managers accept lower occupancy to maximize overall revenue (ie. leaving rentable apartments off the market for short periods of time), which is anti-competitive.

In the same vein, the algorithm also encourages lease end-dates to be staggered to smooth out vacancies, which is also anti-competitive.

RealPage also supports additional communication between users (ie. landlords), where collusion-y conversations might be expected to happen.

While we’ll get into the strength of each claim shortly, what I mostly want to flag here is that ProPublica makes no allowance for price discovery as a positive (or at least neutral) market function. The closest they come is quoting someone who makes this argument—which they do starting in the main article’s 91st paragraph:

But the software’s supporters say it’s not driving the nation’s housing affordability problem.

Though soaring rent is giving the industry a “black eye,” Campo [the CEO of one of YieldStar’s earliest users] said, the culprit is a lot of demand and not enough supply — not revenue management software. The software just helps managers react to trends faster, he said.

“Would you rather do your work today on a typewriter or a computer?” he asked. “That’s what revenue management is.”

Using software like YieldStar is “taking what we used to do manually on a yellow pad and calling people on the phone and putting it on a codified system where you take the errors out of the pricing,” he said.

Indeed.

But as I touch on again and again in this newsletter, including “both sides” is meaningless if you use framing and ordering to drastically weaken one side. If you read this coverage for yourself (I recommend it!), judge how interested they seem in real fairness.

Case in point, this is the article’s 25th paragraph (below two folds / ad breaks):

What role RealPage’s software has played in soaring rents — which in the decade before the pandemic nearly doubled in some cities — is hard to discern. Inadequate new construction and the tight market for homebuyers have exacerbated an existing housing shortage.

“Hard to discern”. Aka, the main charge from their headline (“Rent Going Up? One Company’s Algorithm Could Be Why”) may indeed by wrong. But oh well, they offer this half-hearted caveat some 900 words in, so it’s fine.

Oh, and the line immediately after:

But by RealPage’s own admission, its algorithm is helping drive rents higher.

And this is where we’re going to shift now to more direct misrepresentations.

Bad faith journalism

Ok, so what exactly did RealPage say about driving rents higher? Here’s the direct quote ProPublic uses, from a now-deleted marketing page (archive copy):

“Find out how YieldStar can help you outperform the market 3% to 7%.”

Notice though that—and this is crucial—“outperform the market” is not at all synonymous with “drive up the price of average rents in said market”!4

As the marketing page says right before the quoted bit:

When the market is slowing, prices are adjusted to maintain occupancy, but still maintain a revenue premium. When the market is up, YieldStar pushes higher rents reflective of what the market will bear.

What this says in plainspeak is that the software avoids human error. Instead of letting managers get overly panicky or greedy, it promotes pricing that’s rational to conditions—whether they happen to be going up or down. Selling goods for the maximum price that “the market will bear” while minimizing spare inventory isn’t some nefarious evil. It’s literally Business 101.

That property managers who use algorithms will outperform managers who don’t is hardly news. It’s exactly what we’d expect! (Though of course this advantage declines as more managers use the same software. You’re just not going to find mention of that in a software company’s marketing materials for obvious reasons!)

Anyway, there are more examples of this bad faith framing:

The software’s design and growing reach have raised questions among real estate and legal experts about whether RealPage has birthed a new kind of cartel that allows the nation’s largest landlords to indirectly coordinate pricing, potentially in violation of federal law.

Experts say! Cartels! Violating federal law! Potentially!

Note that one of their own experts, in a 2017 speech that they link to, says this of cartels (emphasis mine):

A cartel is nothing more than an agreement among a group of competitors to fix prices or output so that prices can be maintained above competitive levels.

Right, actually fixing prices above market rates is bad! But…is that happening?

In the article’s 9th paragraph, we’re given an almost-concrete example of this supposed fixing:

In one neighborhood in Seattle, ProPublica found, 70% of apartments were overseen by just 10 property managers, every single one of which used pricing software sold by RealPage.

They then offer some specifics far later in the article:

To see how rent-setting software can make a difference, look no further than Seattle, where over the last few years rents have risen faster than almost anywhere in the country, some studies show. …

The trendy Belltown neighborhood, with its live music venues and residential towers, had 9,066 market rate apartments in buildings with five or more units as of June, according to the data firm CoStar and Apartments.com. Property management was highly concentrated: The ZIP code’s 10 biggest management firms ran 70% of units, data showed.

All 10 used RealPage’s pricing software in at least some of their buildings, according to employees, press releases and articles in trade publications.

Ok, so let’s unpack this:

This is about a single zip code, aka a very small data sample (presumably the most extreme one they find).

We then shrink down to a subset of buildings in this zip code

We then focus on RealPage-using property managers in this subset

But we have no idea how many of these units either report prices into YieldStar, nor how any pricing recommendations here were used

Worse, we also have no idea when these property managers used YieldStar, or if they still do. And it turns out some of this data is super old.

They give us only one building-to-building comparison. Starting with the one that raised rents:

The Fountain Court apartments, 320 units clustered around a courtyard with a fountain, are about a half-mile from Amazon’s corporate headquarters. The building is owned and managed by Essex Property Trust, whose executives told investors in a 2008 earnings call that they were implementing YieldStar in the trust’s apartment buildings.

Ok, so 14 years ok they used YieldStar. Maybe they still do. Maybe they don’t! And how sure are we are that they used it for all their buildings even then?

Anyway, ok, what’s the sin here?

At the Fountain Court, rent has risen 42% since 2012, CoStar data shows — steeper than the 33% average increase for similar downtown buildings.

Note that the comparison is…a different neighbourhood! Similar buildings in different areas do indeed often increase in value at different paces.

Anyway, it gets worse. Here’s the comparison building from the same zip code:

About six blocks away, rent has not gone up as dramatically at The Humphrey Apartments, a historic six-story brick building with 74 units.

John Stepan, a writer for a tech company, moved into a studio in the 1923 building a little more than a year ago. It was small, but he liked the high ceilings, hardwood floors and farmhouse-style kitchen. He had secured a COVID deal, too: one month free, with rent of $1,295 a month after that.

A few months before his lease was up, the building notified him that rent would increase by $50, which amounted to about a 3.9% rise. “It was surprisingly low,” said Stepan, who left only because he found a condo to buy nearby.

Ok, so we have a data point! Except ProPublica fails to mention that said building has a 2.2/5 rating on Google (compared to 3.6 for Fountain Court)! Of the nine reviews available, only two are positive. And one of those is from…drumroll…John Stepan.

Taking this together, they cherry-picked the most extreme concentration of (maybe) YieldStar users they could find, then quantitatively compared pricing in this single zip code to a different zip code, and anecdotally compared one building within the zip code to a building which has six one-star reviews out of nine total.

Oh, one final detail. When I looked up the Fountain Court building, they’re offering a free month:

This is symbolic of the problem with this coverage. If this building manager is indeed using YieldStar, they’re going to spot market downturns fast too, and will offer discounts and other enticements to qualified renters before less aware competitors. Good price discovery works both ways! One just makes for a less sexy article.

Anyway, let’s close this out by looking at how YieldStar’s functions line with up current US antitrust law.

The Sherman Act

(Mandatory caveat here that I’m not a lawyer. I’m making best efforts at summing the law based on my reading of past cases and the underlying first principles. Corrections welcome.)

The reference legislation here is Section 1 of The Sherman Act:

Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal.

Put more simply, collusion that reduces competition is a no-no.

While there’s a lot of relevant case law here for those so inclined, let’s look quickly at each of ProPublica’s five concerns (which map well to the claims in the lawsuit), using my wording from above:

This data sharing shouldn’t be allowed, as it enables possible price fixing.

Quoting the FTC, a setup like RealPage’s “cannot alone establish” a breach here. To cross the line, “competitors must agree amongst themselves to the restraint of trade”.

Basically: establishing the preconditions for possible price fixing isn’t itself a crime. Proceeding to actual price fixing is a crime. Just improving price discovery is fine.

The way YieldStar’s algorithm suggests prices (based on this data) is either price fixing or close enough.

To make this case, you’d likely have to prove that the algorithm does something more than suggest the same pricing that any rational actor would infer from the pricing data. Using a calculator isn’t a crime. If all YieldStar does is crunch numbers in the same way any reasonably-bright property manager would do manually, it’s likely fine.

What’s remarkable to me is the ProPublica has (or at least offers) zero real data about prices in YieldStar buildings vs local comparables. Property managers that use various RealPage products, including YieldStar, might outperform their counterparts by 5% or whatever, but that doesn’t mean average rent charged was 5% higher. Reacting to market trends faster—in both directions—will lead to outperformance, but won’t necessarily have any impact on average pricing over say a year.

The algorithm occasionally recommends that property managers accept lower occupancy to maximize overall revenue (ie. leaving rentable apartments off the market for short periods of time).

Artificially reducing supply would be a problem if widespread. But what’s less clear is how often YieldStar makes these recommendations, and for what durations. The only example ProPublica provides is of one property manager who went from “seeking” 97-98% occupancy to being happy with 94-96%. But this is more “this manager learned the very very old concept of net optimization”5, not “there’s this one illegal new trick”.

In a case where: (a) YieldStar had monopolistic control of a market and (b) it encouraged all landlords to hold back units, sure, that’s a problem. But the only context in which this would make financial sense for them is to do this for any length of time is if they could block new supply from coming on the market.

Though note the next possible exception.

The algorithm also encourages lease end-dates to be staggered to smooth out occupancy.

This one is admittedly interesting to me. But we need to distinguish between two things here:

YieldStar encouraging individual buildings to stagger leasing dates as a basic function of good management for that building.

YieldStar using its data to recommend specific staggering strategies to customers so as to smooth out the entire local market.

The first is obviously fine. The second? Much murkier. Again we’re in the territory of “this is the same conclusion a bright person would reach using manual methods”. But unlike general rent prices, this data is more private by nature. Property mangers have called around doing surveys of rent prices since rent existed. But when specific leases end is more proprietary, and I can kinda see the potential concern here.

The lawsuit (via articles 8-9) suggests that YieldStar is doing this second thing, and also that it recommends eg. “hold some units back this month, as too many buildings in the area are experiencing above-average lease renewals”. If true, does this cross the line? I honestly don’t know. It has a similar function as price discovery (more information = more efficiency = more fairness), so it doesn’t feel overly wrong as a concept. But I suppose some judges could disagree.

RealPage also supports additional communication between users (ie. landlords), where collusion-y conversations might be expected to happen.

This seems a wholly moot point to me, as this communication could happen just as easily anywhere else? There are a million others events and forums where these property managers naturally mingle. While you could argue that RealPage offers them a place to talk to other YieldStar users specifically, this isn’t super private info.

More generally though, I don’t understand the basic implication of collusion. You can’t really fix prices unless you substantially control a market (in this case at least an entire neighbourhood). If you only collectively own 70 of 100 buildings in a zip code, you can theoretically raise rates in concert. But the owners of the other 30 will just…not do that? And the conspirators will just lose good tenants? And even if you own all 100, you also have to be able to cut off the ability of other people to build more.

On that note, let’s close with this pair of tweets:

While rents are now falling in most major US markets, there’s a simple cure for when they start going back up again: just build more units.

If ProPublica wants to point out the real villain behind too-high rents, let’s talk about NIMBYs and how they are very, really, actually reducing competition by making it difficult-to-impossible to build anything but single-family homes. That’s the real story, not the fact that some property managers know a week early to adjust pricing to reflect supply gaps being caused by bad policy.

Two points here for fairness: (a) Some readers felt my linked pieces on ProPublica’s billionaire taxation series were wrong in various ways. See my extensive footnotes in said pieces for why I disagree quite strongly. While I awarded a few quite minor corrections, most of the criticisms were rooted in (I think honest) misunderstandings of an admittedly complex topic. (b) ProPublica only refused to continue engaging with me personally in that one case I linked to. (Said link includes my full correspondence with them, which I think is really illuminating.) I stopped approaching them after that. But they received tons of public pushback to their taxation series, and largely refused to engage with that too.

This isn’t a minor point, and I think ProPublica needs to be clear here about exactly when they began their investigation and what instigated it. In particular, was ProPublica set on the scent by the nonprofit behind this lawsuit? While it’s obviously fine for a nonprofit to tip off a newspaper to potential wrongdoing, this is much murkier if this tip is designed to advance / enhance potential litigation. (While I don’t mean to imply that ProPublica necessarily did anything untoward here, transparency is their own best defense.)

I get a kick out of how ProPublica used the words “secret” and “mysterious” in their coverage. A product used for 20m unit is only a secret to people who have no understanding of the space, and YieldStar’s algorithm is only mysterious to those who don’t understand the basics of how asset optimization works.

I suppose it’s an easy conflation to make. But it’s easy for one property manager to outperform their peers without having much effect on average prices. They just need to react to pricing trends faster. Also, the sum of financial performance across all local property managers is also not synonymous with average prices. On the revenue side, they might just be more efficient at limiting vacancies. And on the profitability side they might be using other RealPage (or whatever other company’s) software to decrease costs for application processing and other stuff that’s more expensive to do manually.

There’s an absolutely nutty part of the lawsuit (section 9, on page 4) that touches on this. But this is not at all, all, all a new tactic. You can either optimize for selling out your inventory, optimize for selling units at the highest price, or optimize for the highest amount of total revenue (or net profit). Again, this is super 101.

Breech instead of Breach.

1. The rental market is nothing like the stock market. Rent transparency is entirely asymmetric. There is no YieldStar for renters. Such asymmetry cannot make a fair market. Moving also involves significant transaction costs and upheaval, unlike zero-fee stock trades.

2. An almost perfect analog to YieldStar is the airline ticket reservation systems and the DOJ sanctioned airlines for almost identical anticompetitive behavior 1994. https://www.justice.gov/archive/atr/public/press_releases/1994/211786.htm

3. You can most certainly have antitrust violations without explicit price fixing: payments to delay generics and employee non-poaching agreements among Google, Adobe, etc. are just two examples of many deemed to have violated antitrust laws without explicit collusion or price fixing.

4. Scale and transaction costs matter. YieldStar makes trivial what would previously have required dozens or hundreds of phone calls and hours of work to collect a tiny fraction of the data in an Excel spreadsheet that would be obsolete in a month. Automating this process can distort the rental market just as algorithmic trading has distorted the financial market.

These are just the factual problems with your naive take. The much bigger problem is that you wrote this without testing your own biases, opting instead for snark, which calls into question your intelligence and supposed objectivity.