What really happened in Uvalde

A comprehensive look at new evidence, open questions, and top takeaways.

Last Sunday, a Texas House investigative committee released an 81-page interim report on the Robb Elementary shooting. It was illuminating, if ultimately not quite satisfying—including many questions marks where we should have periods by now. But it at least provided a clearer picture than we’ve had to date.

Another detailed report [download only] was also released by Texas State University, which houses the state’s chapter of the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training (ALERRT) program. Strangely, this one got much less press coverage.

Building on both reports and other primary sources, this post covers four things:

What we’ve learned since the early reporting cycles

Open questions / unresolved controversies

Non-journalistic failures

Journalistic failures (and plausible fixes)

We reward corrections. See something wrong, misleading, or unfair? Use our anonymous Typeform or drop a comment in this post’s dispute doc.

To make my biases explicit: I’m Canadian, and I greatly prefer our gun regulations to America’s. But I won’t be getting into the larger gun debate here.

What we’ve learned

(Unless otherwise noted, factual claims come directly from the two reports.)

Early engagement

The carnage happened fast. The shooter entered the building at 11:33:00, and his first classroom at 11:33:32. He’d largely stopped firing by 11:36:04. The audio evidence suggests he only fired six more shots thereafter (excluding those directed at officers outside). More on those six shots later.

Three officers entered the building from the NW door at 11:35:55, followed by four more from a south entrance five seconds later. They advanced to the classroom doors within just fifteen seconds, but took fire immediately.

Two of those officers were injured by fragments (not clear how seriously), and they elected to temporarily withdraw to regroup.

One of them, Lt. Martinez, then immediately headed back towards the classrooms. But apparently no one followed, so he abandoned the effort.1

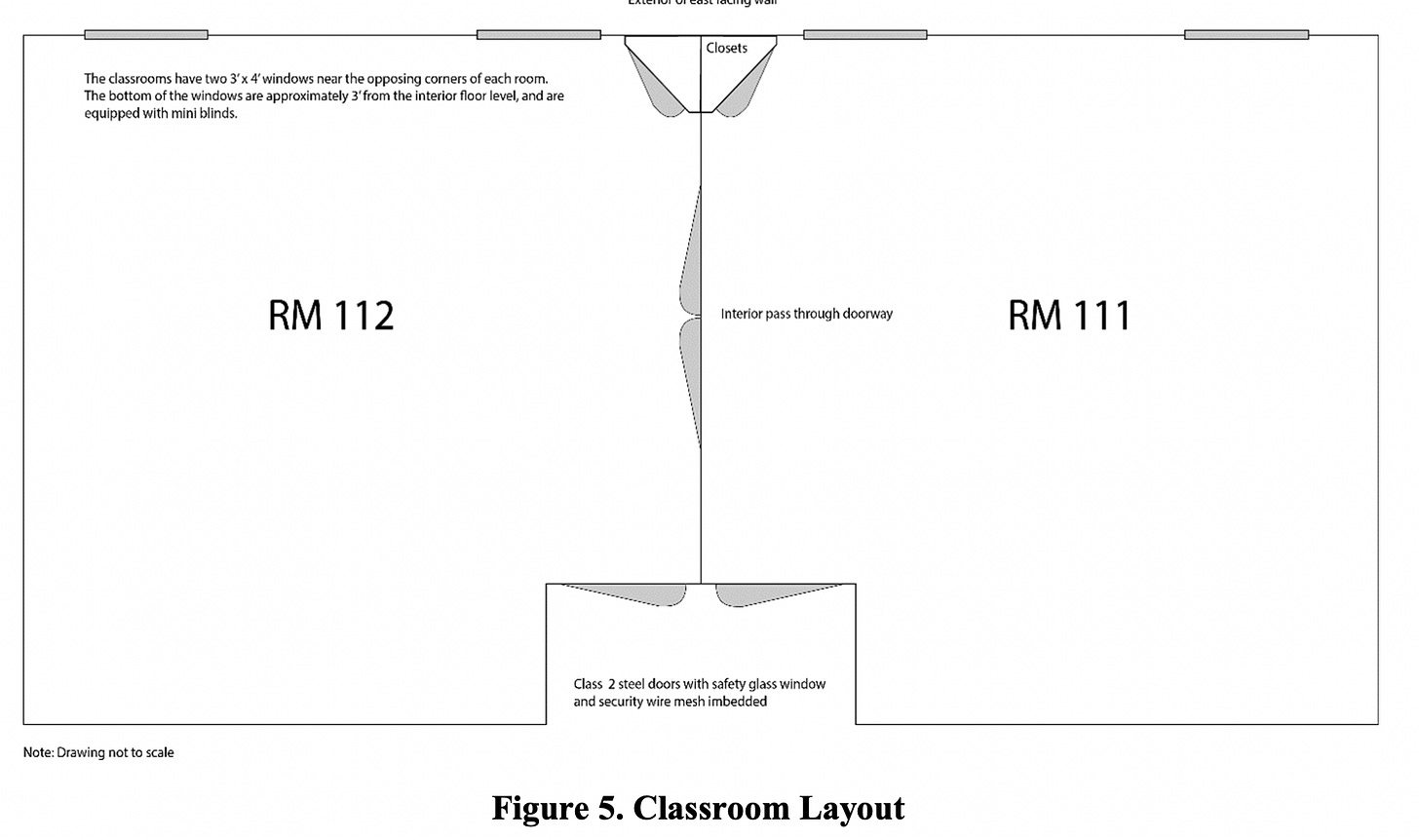

Note that bullets were mostly coming into the hallway (and nearby classrooms) through the walls, which were just sheetrock and fiberglass insulation. The classroom doors were also only “level 2” (see grading system relative to bullets here), where a “level 7” door is required to stop AR-15 ammo.2

Causes for slow action

There seem to have been four big blockers, judge them how you will:

Fractured leadership. There are two Uvalde police forces: one for the city and one for the school district. The latter only had a max force of a half-dozen officers, but had presumed jurisdiction. Its chief, Pete Arredondo, was nominally in charge, but seemed ill-equipped for the situation. Unhelpfully, the chief of the larger city force was out of town that day, leaving an even iller-equipped Lieutenant as acting chief.3 Both reports describe a broken chain-of-command, eventually resolved by independent action from a United States Border Patrol Tactical Teams (BORTAC) unit. The latter showed up at 12:15, and breached the classroom on their own initiative at 12:50.

Broken information flow. Mirroring the fractured leadership, information flow was at best uneven. It’s not clear which officers knew when that survivors were still in the affected classrooms. Arredondo seemingly treated the situation as “contained”, which is only permissible by ALERRT standards if you believe there’s no active shooter / no vulnerable victims. His argument (see PDF pages 55-57 here) was that his focus was on evacuating other classrooms while the shooter was barricaded in Rooms 111/112. It’s unclear when he learned with certainty about the survivors trapped therein.

Classroom entry. The school had a keys problem (more on that later), and it took them a long time to find a master key that worked on other doors. (Breaching via other means was considered high risk, as it gave the shooter more notice and increased the odds of casualties.4 They also had no way of determining if the doors were locked without putting someone in harm’s way.)

Insufficient shielding. Four ballistic shields arrived (at 11:52am, 12:03, 12:04, 12:20), and apparently only one of them was rated for rifle ammo (not clear which one). In the absence of an appropriate shield, no breach was ordered. (Whether they should have gone in without one is something we’ll address later.)

Again, weigh all that how you will.

False alarms

While some of the staff shouted warnings at the shooter’s approach (plus the gunfire outside was obviously audible), the school’s formal alert system had a massive Boy Who Cried Wolf problem: it had gone off 47 times for non-emergencies since just February.5

There was also a problem of teachers not having phones out/on, else having poor wifi connectivity. So the alert system was functionally useless. The school principal, likely gripped by panic, also didn’t think to use the PA system.

The shot not taken

One thing that the ALERRT report gets wrong that the House report is clearer on: claims that an officer had the shooter in their line of fire while still outside the school were wrong. The officer didn’t get clearance to take the shot, which was good, as said individual turned out to be a school coach.

Unlocked doors

Contrary to many early reports, the outside door that the shooter used to gain building access wasn’t propped open. It had been earlier, but a teacher shut it a little over three minutes before the shooter entered. It just failed to auto-lock.6

That said, all exterior doors to the building in question (the school’s isolated western wing) were found to be unlocked. The House report found that the school had a lax culture on that front (more on that later).

Most classrooms doors were locked. Room 111 was known to have a latching problem, which was likely what let the shooter inside the twin classrooms. (We’ll cover “which door did he actually enter” later on, but the evidence leans strongly to 111, from which he had unfettered access to 112.)

Officer Ruiz

Ruben Ruiz, the officer seen on video checking a phone with a Punisher logo as its background, was confirmed as the husband of Eva Mirales, one of the two teachers murdered in Room 112.

Confirming early reports, we now have video of Ruiz being (gently) turned away from re-entering the hallway at 11:56am7, having presumably just learned from his wife that she was wounded. Whether his gun was taken is unclear.

His choice of phone background aside, I see nothing to indicate that Ruiz did anything wrong. He checked his phone, sure. He was looking for updates from his wife! Who wouldn’t? He also didn’t storm the classrooms, true. But that wasn’t his call. He was—appropriate for his emotional involvement—deferring to his colleagues and superiors. Their poor choices weren’t his.

Open questions / controversies

The question of cowardice

The officers’s collective slowness spawned many a take like this one:

These takes then intensified when it became clear that a total of 376 officers were on the scene. How could that many LEOs all be too cowardly to just go in there?

While I’ll leave the value judgment here to the reader, it’s worth noting that there was a classic Mouth of Thermopylae problem: all 376 officers couldn’t just bullrush the shooter; there was just one point of entry,8 and someone had to breach it first.

Consider:

Bullets were coming through both the door and nearby walls

They initially didn’t have a shield capable of stopping rifle fire

They believed that the shooter had a direct line of fire, and would thus immediately fire at whomever breached the door first

This door breaching (without a key) was expected to be…not fast

No matter how many officers you stack in a line, someone has to go first

Going in also meant disregarding/disobeying the chain of command

I’ve chewed on this for several days and still don’t know exactly where to land on it. I guess I lean towards cowardly? You certainly hope in a group of 376 that you have at least one willing to take the risks of going first with only a non-rated shield. But if you were to assess their likelihood of dying, that number is also not going to be low.9

There’s a wide middle ground between heroism and cowardice, and I think most of us—including most LEOs—live in that middle place. That’s deeply unsatisfying. We like to imagine first responders as the bravest of us. And sometimes they are. But when they aren’t, are they cowards? Perhaps. Again, I leave this to the reader’s judgment.

Lives sacrificed

How many people died because of the slow response? We don’t have medical conclusions yet re: those who initially survived but later died of their injuries. Perhaps some of them could have been saved. We’ll know more in time.

A related question is how many more were shot in the intervening time. The shooter fired a total of six not-towards-the-police shots after his initial barrage: one at 11:40:58am, one at 11:44:00, and four at 12:21:08.

We know that one of the first two was him shooting Arnulfo Reyes—the teacher in Room 111—an additional time (who incredibly survived). The other five have yet to be accounted for. But the final four happened within about a minute of one of the 911 calls. If those indeed were the shooter punishing the caller, that’s going to sit long and heavy with those who decided to wait to go in.

(For what it’s worth, the ALERRT report says on PDF pg. 20 that any of these additional firings should been impetus to assumes lives were still at risk.)

Room 111 v. 112

Which door did the shooter enter? Here’s a useful visual from the ALERRT report:

We have heavy anecdotal evidence that the door to 111 often didn’t latch properly, which both reports assume was how the shooter entered. Curiously though, teacher Arnulfo Reyes—the sole survivor from 111—has been clear in interviews that he thinks the shooter entered 112 first.

The ALERRT report gives us a plausible harmonization, in that it says (PDF pg. 7) that the shooter first fired from the hallway towards both classrooms, some eight seconds before entering his first classroom (likely 111). So from Reyes’s perspective those first shots from the hallway may have appeared to be happening within Room 112.

Intervening activity

What did the shooter do during his roughly 70 minutes of waiting? It seems he stayed mostly in Room 111, in which only Reyes survived. Perhaps this will always be a mystery. Perhaps it doesn’t matter. We do have reports that the shooter called out tauntingly to the police at least once. But I hope investigators drive for answers here, as there very well could be more meaningful data here.

Non-journalistic failures

To add to what we covered in the first section:

How do you get 376 officers from 23 agencies and exactly one rifle-rated shield between them—when virtually all mass shooting they’d need to respond to are by AR-15s or equivalents? Why don’t schools have these on site?

It was an open secret that Room 111 didn’t latch properly. But no work order was ever filled out?

Why was the school’s chronic key shortage10 not addressed earlier? Teachers regularly propped open both internal and external doors because so many substitutes didn’t have keys.

Why retain an alert system for major incidents when it has effective false alarms multiple times a week?

It’s worth noting that almost nothing that went wrong was a matter of a missing or inadequate policy. At every turn, the policies were just halfheartedly embedded and enforced. This should give other school districts pause.

Hire a DRI

There is one concrete policy reform we should push for: a single agency / government czar for mass shooting preparedness, including threat evaluation.

Consider what we know about the shooter:

If you jot down a list of untreated traumas and grotesque behaviours that might plausibly collide to make someone a likely school shooter, then compare your list to the shooter’s bio (PDF page 32ff), you’ll note that this one wasn’t a tough judgment call. He was a one-man red flag parade.

Multiple people across unconnected groups called him “school shooter” as a nickname. He tried to buy guns illegally at 17, ordered them legally the day he turned 18, and went shooting the morning after his ammo came in the mail.11

Though his case was more blatant than some others, it’s hardly an outlier. But the universal theme is that reports about escalating dangers of these beyond-troubled teens often go nowhere. While no policy will reduce these shootings to zero, appointing a directly-responsible individual (DRI) gives us our best chance. Reports should be centralized to a group empowered to at least: (1) refer cases to mandatory counselling, and (2) temporarily restrict legal gun purchases in the interim.12

Journalistic failures:

Naming evil

It’s been about two decades since we’ve reached a consensus that naming school shooters in the media is bad. There's roughly zero civic upside to including their name or any identifying details in public reporting.13 Call them “the shooter”, “the Uvalde coward”, whatever convention you want. But print that which empowers readers to make better decisions, not that which gives notoriety to the wicked.

Last year, NPR published (in their opinion section) an appeal “to develop standards that guide journalists and help the audience understand when it is appropriate to name the shooter, and when to avoid it.”

My thoughts on it:

The standard is easy: just never fucking name them.

Why did NPR green-light this op-ed and then do nothing with it?

Why hasn’t even one major paper just shown leadership here?

How many times do we have to read details like this (from the House report):

The attacker often connected [dates in May] with doing something that would make him famous and put him “all over the news”.

Why did we grant him his wish?

Over-deference to authority

One unhelpful part of the story was that official sources kept contradicting themselves and giving out (possibly inadvertent) misinformation. The larger issue though is that this happens every time, and major papers still just uncritically print what’s on offer as if it were somehow certain fact.

Virtually all historical data we have points towards the wisdom of taking early official statements as provisional. Some papers were smart enough to qualify updates with “here’s what’s claimed so far”, but far too many were overly declarative.

I’m not arguing that journalists shouldn’t print official statements as provided. They certainly should. Just with some mix of caveating and explicit commentary about the obvious gaps and contradictions therein. Though of course though this would require them each developing their own informed points of view to do so…

The clickshare problem / the static article problem

We covered this in Tuesday’s post, but there are two broad problems here:

Every outlet wants to cover trending stories, and few care to do it well. Lots just lightly rewrite the work of others, and it’s often impossible for readers to tell if they’re reading original reporting or almost-plagiarism.

Even for those producing good original reporting, where can readers turn to make sense of the full scope (so as to avoid having to read a dozen articles)?

While I outlined some thoughts on solving the first problem Tuesday, I want to flag a good example of journalism doing the second thing well: Texas Tribune’s timeline.

I could nitpick: it doesn’t have an edit history, and only covers so much. And it’s unclear if they’ll keep updating it. But still: so much better than the average! I hope Google works on making that type of article appear first in their News carousel.

Excessive meekness

Major papers have incredible collective influence when they row in the same direction. Why haven’t they used this power to publish a joint op-ed calling for the lowest-hanging solutions—like a mass shooting preparedness DRI, or at least a total moratorium on using shooters’s names?

They can’t really move the needle on the gun debate. We know that. But we don’t need them to get that far; we just need signs of life.

He later helped evacuate kids from other classrooms through windows, and was apparently part of an in-hallway support column when the doors were finally breached.

Or at least that’s true of most AR-15-style rifles, which google tells me fire 5.56×45mm rounds. Per PDF page 38 here, all the shooter’s ammo was 5.56mm. Some AR variants fire other calibers. But from the first responders’s POV, the door was not rated to stop heavy rifles, and bullets were apparently going through it.

Take this damning paragraph from the House report: “Lt. Pargas, who was one of the earliest responders, testified that he was never in communication with Chief Arredondo, and that he was unaware of any communication with law enforcement officers on the south side of the building. He told the Committee he figured that Chief Arredondo had jurisdiction over the incident and that he must have been coordinating the law enforcement response—and that the Uvalde Police were there to assist. He did not coordinate with any of the other agencies that responded... Lt. Pargas did receive a phone call from the chief of the Uvalde Police, who was out of town on vacation, who called to tell him to set up a command post right away. Lt. Pargas testified that he went to the back of the funeral home to start a command post, that the funeral home provided an office, and that then he went back outside to try to keep up with what was going on. This did not result in the establishment of an effective command post.”

From the House report (PDF pg. 64): “According to his statement, Cdr. Guerrero attempted to pry open a door in the hallway to see if the Halligan [breaching] tool would work. He determined it would take too long and dangerously expose an officer to gunfire coming from inside the classroom. He observed that the classroom doorway had multiple holes consistent with bullet holes, and he did not want to expose or jeopardize the safety and lives of any officers by trying to pry the door open.”

Basically the “false alarms” were for cases where illegal border-crossers abandoned their vehicles at a nearby highway junction. Most teachers saw no material risk in these incidents, and ignored the alerts accordingly. Discussion on PDF pg. 28 here.

Though from the ALERRT report: “Even if the teacher had checked to see if the door was locked, it appears that she did not have the proper key or tool to engage the locking mechanism on the door.” Bad design!

This is based on the video timestamp. But I note that the ALERRT report says multiple times that this happened at 11:48:18. I don’t know how to reconcile that.

Technically they could have also entered through 112, but the doors to 111 and 112 were inches apart. A rational shooter would stand near the interior door that split the two classrooms, ready to shoot at whichever entry door they breached. As it happens, the shooter didn’t do that. But it was the safe assumption at the time.

The ALERRT report didn’t assign a probability, but did say (in general of them breaching without adequate protection): “there would have been a high probability that some of the officers would have been shot or even killed.”

From the House report: “The manufacturer discontinued production of the door locks used at Robb Elementary. While the school district had acquired a supply of key blanks at the time the locks were purchased, that supply was gone by May 2022.” So find new blanks or replace the locks?

It seems very probable that this was his impetus to shoot the day he did, and not his fight with his grandmother over his phone bill. See PDF page 41 here.

Ideally, this group interfaces heavily with local school counsellors, police, etc. You need local participation. But you also need federal power to remove roadblocks and pour in necessary resources (say, not requiring the local school to pay for any mandatory counselling). Some will argue that the FBI serves this function today, but like, look around at the last 20 years? Even if they stopped some shootings that we don’t know about, the system seems chaotic and bad. Also, go try googling “how to report a potential school shooter” and imagine how you’d parse the results as a teenager. There should be exactly one link at the top of google, and it should be a mix of simple, thoughtful, and reliable.

NPR managing editor Gerry Holmes argues here that plausible upsides are “to help our audiences understand any possible motives” and “to help explain what happened as we report out the story”. C’mon! We have investigators to investigate motives. Arming a million smartphone detectives (who frequently identify the wrong person!) helps exactly nothing.

This may seem totally out of place but I just randomly found you from a comment like and I think our areas of interest are strongly aligned. Care to email me? I just subscribed.

You use "breech" when you meant "breach" in lots of spots, might want to fix that.