Lucy Letby's Verdict and the Internet's Missing Piece

A review of The New Yorker’s recent reevaluation of an infamous UK murder trial, plus a vision for a new approach to presenting evidence to readers.

Legal disclaimer: In respect of British law, any reader living in an area of England subject to jury selection for Lucy Letby’s upcoming retrial is advised to not read what follows. (For readers elsewhere, we’ll cover the logic and impact of these laws later on.)

The first section of this piece is about a particular legal case, that of British former nurse Lucy Letby, who was convicted last year of seven counts of murdering babies in their hospital beds, along with seven additional counts of attempted murder.

The second section is about a much larger question: when a major trial concludes, how can the public know with reasonable certainty whether to be confident in a given verdict? In a world in which juries and journalists are sometimes right and sometimes wrong, what would a better system of public information look like?

[EDITS 09/23/24]

I’ve added a reader note to the Document Stashes section below.

While I have no immediate plans of writing more on this case, curious readers can follow updates from the ongoing UK government inquiry here.

I also used fresh eyes to clean up a few grammatical nits while in here, though without changing meaning anywhere.

Bias & Disclosures: I think that justice has a strong correlation with free speech and free inquiry. I’ve elsewise covered The New Yorker’s fabled fact checking department before (here, here) to mixed findings. My subjective take is that they did diligent work on this one.1

Corrections: As always, we reward corrections. See something wrong, misleading, or unfair? Use our anonymous Typeform or drop a comment in this post’s dispute doc.

Case Primer

Starting in the spring of 2015, Lucy Letby spent a little over a year2 working with intensive cases in a NICU (Level 2 NNU) at a hospital some 45 minutes south of Liverpool, during which time she was found to have carried out or attempted the murder of thirteen separate babies. Barring a successful appeal, she will be just the fourth British woman sentenced to spend the rest of her natural life in prison with no possibility of parole—the strongest criminal sentence available in the UK.

One of two things is true of Letby:

She was indeed guilty of roughly the worst form of crime there is

She was wrongfully convicted of roughly the worst form of crime there is

Given these extremes, it seems ideal for civil society to know for sure which is true.

On the guilty side we have the jury, who, after hearing nine months of evidence and deliberating it for ~110 hours, ultimately reached either majority (10-1) or unanimous (11-0) convictions on fourteen of the twenty-two counts presented to them.3

On the less convinced side we’ve had mainly a few independent skeptics, newly joined by The New Yorker, which published a ~13,000 word investigation last week that outlined a sprawling set of concerns with the presentation of evidence at her trial.

While I can’t personally tell you if the jury got it right or not, my real interest here is the question of whether any outsider can, and the specific difficulties of reaching certainty without either having served in the jury box or investing many weeks of time independently compiling and reviewing all the evidence presented.

Some Brits who’d followed the trial closely have voiced concerns that The New Yorker either ignored or mischaracterized essential claims. Are they right to think so? And what should a newcomer to this case think? To where can they turn to find all arguments for and against the hundreds of specifics on which the case turned?

While there’s a degree to which this is simply an impossible problem (trials wouldn’t take nearly a year if the evidence weren’t ranging and complex), there seems to be room for a much better solution than we have today. And not just for criminal trials, but for most types of controversies where the evidence is (at least mostly) public.

What follows won’t answer all your questions about Letby, nor even most of them. My goal is to dive into the case just enough to illustrate the limits of our current public information systems, and then to pivot to what an alternative could look like.

UK vs. US: Cultural Consequences

(What follows is relevant today because Letby is scheduled for a June retrial on one attempted murder charge that her original jury couldn’t reach a decision on.)

One wrinkle in this particular case is that the UK and US have very different approaches to covering legal trials. For the UK, in broad strokes:

While any trial (including appeals and retrials) is ongoing, it’s considered contempt of court for residents to (1) publicly speculate on whether the defendant is innocent or guilty, (2) refer to any past convictions

During such a period, it’s also generally forbidden for media outlets to publish anything other than factual recaps of ongoing proceedings

These rules obviously reflect cultural preferences not widely shared in the US, where it’s taken as gospel that systems are only as good as the vigilance that keeps them good. Any restrictions on free speech, especially premised on “trust the process”, simply wouldn’t fly there. While it’s not my object to debate which set of preferences are better (and it’s worth noting that the UK is currently reviewing theirs), these rules have introduced some weird complications here:

The New Yorker had to block UK IPs from accessing the web version of their article (though their print version, controversially, went out as a cover story to UK newsstands)

None of the subjects of said article who reside in the UK are fully free to respond publicly to how they were characterized in it

While I don’t fault The New Yorker for the latter (they had no real control over how long the editorial process took and couldn’t anticipate when the retrial restrictions might begin or how long they might last), I’m a little sympathetic to the asymmetry it introduces. An American outlet had a lot of critical things to say about British systems and individuals, and the latter’s hands are for now largely bound in what they can say in reply. It’s unideal, even if not the Americans’ fault.

(A counterpoint is that the free comment period between the end of Letby's trial and the announcement of her retrial was only about a month. That wasn't enough time for an in-depth investigation like The New Yorker's, meaning that everything published over that span was basically "she did it". The same is roughly true for prior coverage, resulting in an infosphere where her guilt has been presumed and contrary voices have mostly been in the far margins.)

Anyway, the larger point here remains the same: one day the embargo will lift and UK residents will be again left to openly ponder whether justice was indeed served. What will they do when that day comes? Where can they turn for full clarity?

The New Yorker, Pt 1: Information Access

(I had a lengthy email exchange with the staff writer behind this piece. She was gracious with her time and answered all my questions in detail and what I believe to be good faith. I appreciate this a lot, and hope readers do as well.)

One aspect of how The New Yorker put their story together is underappreciated: they were able to get their hands on not just internal hospital records, but ~7,000 pages of court transcripts. While this will sound unremarkable to American readers, this is more unusual than it sounds for UK trials. As recounted here, it took the staff writer some six months to win judicial approval to even purchase the transcripts in full. It’s fairly rare for journalists there to ever receive or review them all.

One consequence of this: the public (and anyone writing about this, including me) only has ready access to lesser information. Many Brits listened to a widely popular trial podcast produced by The Daily Mail, else relied on daily digests from the reporters that covered the trial live (nifty index here). These sources, while fairly comprehensive, are also incomplete. Testimonies are compressed and paraphrased, exhibits are omitted, and some quotes are just missing altogether.

Does this mean The New Yorker is necessarily right about any particular claim? No. But they were able to amass some 300,000 words of indexed notes based on precise transcripts, which is a considerable structural advantage. My sense is that many concerns raised about their article may in part be just this difference in information quality. (I looked through a handful of the more popular examples of “this was wrong” and didn’t come across any black-and-white examples that held up. That said, the internet is a big place and some know this story better, so YMMV.)

But even if we grant that they have more info than any other outsider, did they use that trove in an unbiased way?

The New Yorker, Pt 2: Bias

I’m going to focus on four specific details here, none of which are questions of fact per se, but rather of how or why one might frame or omit a given fact—and the effect these editorial decisions have on readers.

#1 - Document Stashes

Lucy Letby had a strange habit of taking home private work documents, having been found in possession of 257 hospital handover sheets. 21 of these documents were found to include treatment notes related to babies from the trial (though not always for days on which anything notable happened to them).

While it’s true that medical staff accidentally take documents home from time to time, as one doctor friend (a self-admitted forgetful type) put it when I asked him about the sheer number here, “this person would be in the stratosphere of carelessness”. 257 is simply well outside any normal band of honest mistake, and at best reflects an indifference to the privacy aspect of patient records control. Some of these documents had also moved with her, and some had been stored at her parents’ home.

[EDIT: Adding a note to acknowledge this tweet, which points to a YouTube video in which a UK doctor, Scott McLachlan, describes encouraging nurses to take home their handover sheets. While I’m unaware of this advice being common throughout the NHS, and while it seems to have been explicitly against the policy of the hospital in question, I note it all the same for transparency. More on this here.]

Now, it’s certainly possible that this was peripheral to the crimes of which Letby was accused. But it’s also possible that it wasn’t. If she is a murderer, it stands to reason that maintaining private access to these sheets could help her eg. prep for potential questioning without being seen accessing permanent in-hospital records—or whatever less scrutable reason. (It is puzzling however that she wouldn’t have burned or shredded them at some point. By the time of her arrest the police had already been investigating the case for a little over a year, which she’d have known.)

Even if leaving out this detail was defensible editorially, many readers may find it reflective of a larger bias towards Letby’s innocence. While it doesn’t make the reporting wrong, and while no article of any length can include everything, these decisions can add up in a reader’s mind.

#2 - Baby E’s Mother

(In this section I’m narrativizing parental testimonies from this trial summary.)

Imagine that you’ve just given birth for the first time, five days ago, to twin boys. They’re still stuck in the NICU, and you still can’t do the one thing you want to do most in the world: take them home. But soon, you’re told. They’re doing better. You’ll all be home any day now. So for the interim you focus on what you can do, including skin contact and feedings. The latter are “non-negotiable” to you.

9pm rolls around, which is feeding time for your older boy. So you grab your expressed milk and take it to his room. To your shock, you hear him screaming on approach and find a nurse in his room, busy at a workstation, not responding to “horrendous” noises that terrify you. And then you notice blood on your son’s mouth.

The nurse assures you it’s all normal, just a tube irritating his throat, and reminds you that your child is in good hands. You accept this and return to the postnatal ward. But something isn’t sitting right, leading you to call your husband at 9:11pm, for a little over four minutes. He tells you there’s no need to panic. The boys are getting better, it’s just a bit of blood, we’ll take them home soon, maybe even tomorrow. He’s working on their new room as you talk to him. You choose to focus on that.

The next time you see your son, a few hours later, he’s in terminal decline. Eight minutes of resuscitation attempts don’t work. Your firstborn is handed to you and your husband to hold as he draws his last breaths. You’re then told that a post-mortem is unlikely to reveal anything, and would delay you taking your baby boy’s body home. So you accept the hardest news you’ll ever receive and decline the autopsy. (But you also request a hospital transfer for your surviving son, which is declined for logistical reasons. The jury later finds that he was intentionally poisoned with synthetic insulin by that same nurse about a day later, which he mercifully survived.)

Lucy Letby and her counsel disputed much of this, insisting that no 9pm visit ever happened, and that whatever call was placed at 9:11pm must have been about something else. A note from an attending doctor (at 10:10pm) notes a GI bleed, but nothing else remarkable. While this doesn’t tell us whether the 9pm interaction happened, it does suggest a limit on any harms inflicted at the time. Did Letby attack him in some mild way—leading to the screams and bleeding—and then escalate later?

Or could the parents just be relying on memories scrambled by both grief and the rage they must have felt when Letby’s crimes were alleged? We have no hard evidence either way. For privacy’s sake, there were no cameras. We have only their respective testimonies, the fact of the phone call, and two other clinical notes. One of those notes is from Letby, which puts the mom’s visit at 10pm instead, after the phone call. The other is from a midwife working outside the mom’s room. The relevant bit reads: “[she] asked me to let her know if there was any [future] contact overnight from the neonatal unit as one of the twins had deteriorated slightly at that time”.

Assuming that the midwife’s note reflects their conversation fairly (we have no concrete reason to doubt it does), how do we reconcile the urgency gap between how the mom framed it to the midwife versus to her husband when those conversations were likely just minutes apart?

The defense proposed that the 9:11pm call was about something else entirely. While the parents both flatly rejected this possibility, it would have been a few years between the incident and finding out that Letby was under suspicion and that their son’s death may have been unnatural. That’s a long time.

It’s possible the mom just didn't want to overreact and stir up formal controversy when she couldn’t be sure anything wrong had happened. These were her first babies, maybe they do scream like that sometimes? And maybe the blood really wasn’t a big deal?

It’s also possible that the conversation with her husband happened first, on her way back to her room, and that she was already feeling somewhat reassured.

Obviously we can't know for sure which of those might be true. But cue an important framing decision: do we pick a side, or do we present both for readers to chew on?

My concern is that leaving this incident out made it harder for newcomers to understand why so many feel certain of Letby’s guilt, and also harder for case-familiar readers to trust the larger narrative here. This was an extremely emotionally compelling bit of testimony, and trial-followers were sure to index on it. To tell the other side of the story? Fine! To omit it? My sense is that this was always going to leave some feeling like there was a thumb unduly on the scale.

#3 - Contextual Criticism

One important paragraph in the article cast aspersion on the competence of Dr. Dewi Evans, an outside pediatrician and court witness who played a significant role in the case (more on that next):

Several months into the trial, Myers [Letby’s lawyer/barrister] asked Judge Goss to strike evidence given by Evans and to stop him from returning to the witness box, but the request was denied. Myers had learned that a month before, in a different case, a judge on the Court of Appeal had described a medical report written by Evans as “worthless.” “No court would have accepted a report of this quality,” the judge had concluded. “The report has the hallmarks of an exercise in working out an explanation” and “ends with tendentious and partisan expressions of opinion that are outside Dr. Evans’ professional competence.” The judge also wrote that Evans “either knows what his professional colleagues have concluded and disregards it or he has not taken steps to inform himself of their views. Either approach amounts to a breach of proper professional conduct.” (Evans said that he disagreed with the judgment.)

Ok, so three things here:

Including this at a time of publication when Evans would be unable to really rebut it seems unfair to me. (Again the timing isn’t anyone’s fault in a larger sense. But including this particular bit in light of the embargo? I can’t get there.)

Evans had explained prior that he hadn’t meant for the letter in question to have ever been used in court in the first place. This was a big thing to leave out!

We aren’t given any additional context on this case, leaving us a bit blind as to what opinions he’d given, under which terms, and what exactly was deficient about them. (Per a local paper the case was a family court custody dispute.)

There’s also a relevant quirk of the UK justice system here, in that expert witnesses have strict requirements to remain independent, irrespective of which side may have hired them. If they fail this, their evidence can be ruled inadmissible. To be so censured is also a significant mark that can interfere with the expert getting future trial work. So it’s not a light charge.

If Dr. Evans indeed had a history of shoddy reports, that’s obviously extremely relevant. But a single anecdote, however unflattering, needs more context to be meaningful. Had he spent a day on that letter? An hour? If we’re going to take this input as relevant in relation to his work on the Letby case (spanning years), answers to these questions would help. I wish we’d gotten them. And that we’d been told about him apparently never having actually submitted said letter to the court.

#4 - Blind Review

This is the longest section. I’m sorry. But it’s also the most important.

This story was, in large part, about data, and about how the presentation of data colors our perceptions—whether as formal jurors or as citizen members of some larger cultural jury. Numbers and diagrams can have incredible communicative power, as they did in this case. But just because data is alluring doesn’t mean it’s either wrong or inappropriate!

Consider this excerpt from a paper co-authored by Richard Gill (a loud pro-Letby voice4), written in reference to a similar case involving another convicted British nurse, Ben Geen. A major factor of Geen’s trial was that his shifts coincided with a cluster of anomalous incidents involving mysterious respiratory arrests (which he was later found guilty of causing via various injections).

They [two experts] were both definitive that a “pattern” could not be established without statistical analysis and that it would require further information, and in particular, requires blinding of medical experts, who should evaluate whether or not events were suspicious without knowing whether or not Geen was present.

I agree with both parts of this! It’s essential to never just assume that a weird cluster of events can’t be explained by either chance or some local non-obvious phenomena that isn’t criminal. And one good way of ensuring that any data is useful is to blindly sort events as suspicious or non-suspicious without any reference to fixed suspects or whom might have been working when.

Thing is, this is exactly how Dr. Evans approached the Letby case. And though The New Yorker doesn’t argue the opposite, it also nowhere confirms this.

What they do say:

The case against [Letby] gathered force on the basis of a single diagram shared by the police, which circulated widely in the media. On the vertical axis were twenty-four “suspicious events,” which included the deaths of the seven newborns and seventeen other instances of babies suddenly deteriorating. On the horizontal axis were the names of thirty-eight nurses who had worked on the unit during that time, with X’s next to each suspicious event that occurred when they were on shift. Letby was the only nurse with an uninterrupted line of X’s below her name. …

But the chart didn’t account for any other factors influencing the mortality rate on the unit. Letby had become the country’s most reviled woman—“the unexpected face of evil,” as the British magazine Prospect put it—largely because of that unbroken line. It gave an impression of mathematical clarity and coherence, distracting from another possibility: that there had never been any crimes at all.

Then later:

Schafer [a law professor] said that he became concerned about the case when he saw the diagram of suspicious events with the line of X’s under Letby’s name. He thought that it should have spanned a longer period of time and included all the deaths on the unit, not just the ones in the indictment.

Here’s the diagram in question (it has 25 incidents vs. the quoted 24 because it’s a v2.0 where a second incident was added for one of the babies):

No other nurse was on duty for more than 7 of these incidents. While it’s true that Letby was picking up extra shifts, and while The New Yorker argues that Letby was actually only present for 24/25 (I agree that including Baby N’s second incident was a reach5), this is still hugely statistically relevant for a blind evaluation.

Per two interviews (3:55 and 7:54 here + 23:52 and 27:14 here), Dr. Evans had requested notes on all cases that involved a death or collapse between January 2015 and July 2016 (unbeknownst to him, Letby had started working with intensive care cases at some point in the spring of 2015). He claims to have explicitly requested to not be told of any police suspicions or whom was working when. He then whittled down the list, removing incidents with non-suspicious causes, leaving him with 15 (later 176). My understanding is that this maps to the 17 babies (anonymously labelled A-Q) in the above diagram.7 The police then cross-referenced this list with shift charts, which confirmed the pattern. (Dr. Evans’ work was peer-reviewed by a few other medical experts, at least one of whom did his work blind before unfortunately dying. While this isn’t quite the same as independent replication, it’s also not nothing.)

Is this proof positive of any wrongdoing on Letby’s part? Of course not! But it would be irresponsible for the prosecution to not point out the striking correlation. That her defense team could have done more to propose alternate explanations or to identify similar clusters at comparable hospitals where no foul play was suspected is perhaps valid, though also an aside. That’s not the job of the prosecution. Their duty was simply to ensure the evaluation was done blind, which Dr. Evans says they did.

(The defense at least provisionally engaged no fewer than three of their own expert witnesses, including one focused on statistical analysis. For unclear reasons they just never introduced any of their work into the trial. It seems a helpful counterbalance would have been for their own expert(s) to have done the same blind evaluation, both over the same period and extending back some ways to give a baseline.)

From the data we do have (pulling from here):8

In a typical year for this unit, 2-3 admitted newborns would die, or 0.17-0.25 per month. Between June 2015 and June 2016, 14 died. Letby was charged with murdering 7 of them (an 8th died after transferring to another hospital and was charged as an attempted murder instead, which isn’t included in the 14). This leaves seven credited to non-suspicious causes, or 0.54 per month.

One way of looking at this data is that this remainder number is high enough to warrant concern about unrelated issues (eg. sicker babies, mismanagement, poor staffing, some environmental factor, etc).

Another way of looking at it is that two things may have happened at the same time: (1) some combination of bad luck and systemic issues, (2) murder. Given how statistically unlikely this combination was, it was thus super important to have proceeded with extreme caution. But the unusual length of the trial and jury deliberations (and the fact that the jury didn’t reach majority on eight charges) implies that caution wasn’t exactly thrown to the wind.

Anyway, it isn’t that The New Yorker explicitly said that Dr. Evan’s work wasn’t done blind. They just didn’t opt to spell it out. Taken with the above, I’m thus a bit sympathetic to readers who found the article biased toward Letby. I don’t say this to undermine just how much effort was put into it, nor to minimize several of the important arguments it raised. I think people should read and weigh it thoughtfully. But all this does serve to neatly illustrate the point we’ve been building towards: where can readers turn for neutral summaries that show the best arguments on both sides of all the important claims in a case?

A Better Way

While some of the commentary in opposition to the New Yorker’s article has been intense (and I believe in some instances unfair), this is in part due to a structural issue with journalism itself. People who’d closely followed the trial felt like one aspect or another had been omitted or misrepresented, else that some of the arguments raised had already been covered and settled at the initial trial.

As I cover above, I suspect that at least part of this is that The New Yorker simply has more comprehensive data. Though I certainly wouldn’t expect or ask any aggrieved reader to accept this explanation at face value! What they want, I think fairly, is for further elaboration on a point-by-point basis. If they’re concerned about claim X, anything that isn’t a direct response to their understanding of claim X simply isn’t going to get them anywhere. Nor should it. But this is also something that no single article can hope to accomplish!

So one obvious question: why doesn’t an alternate resource exist that allows exactly this?

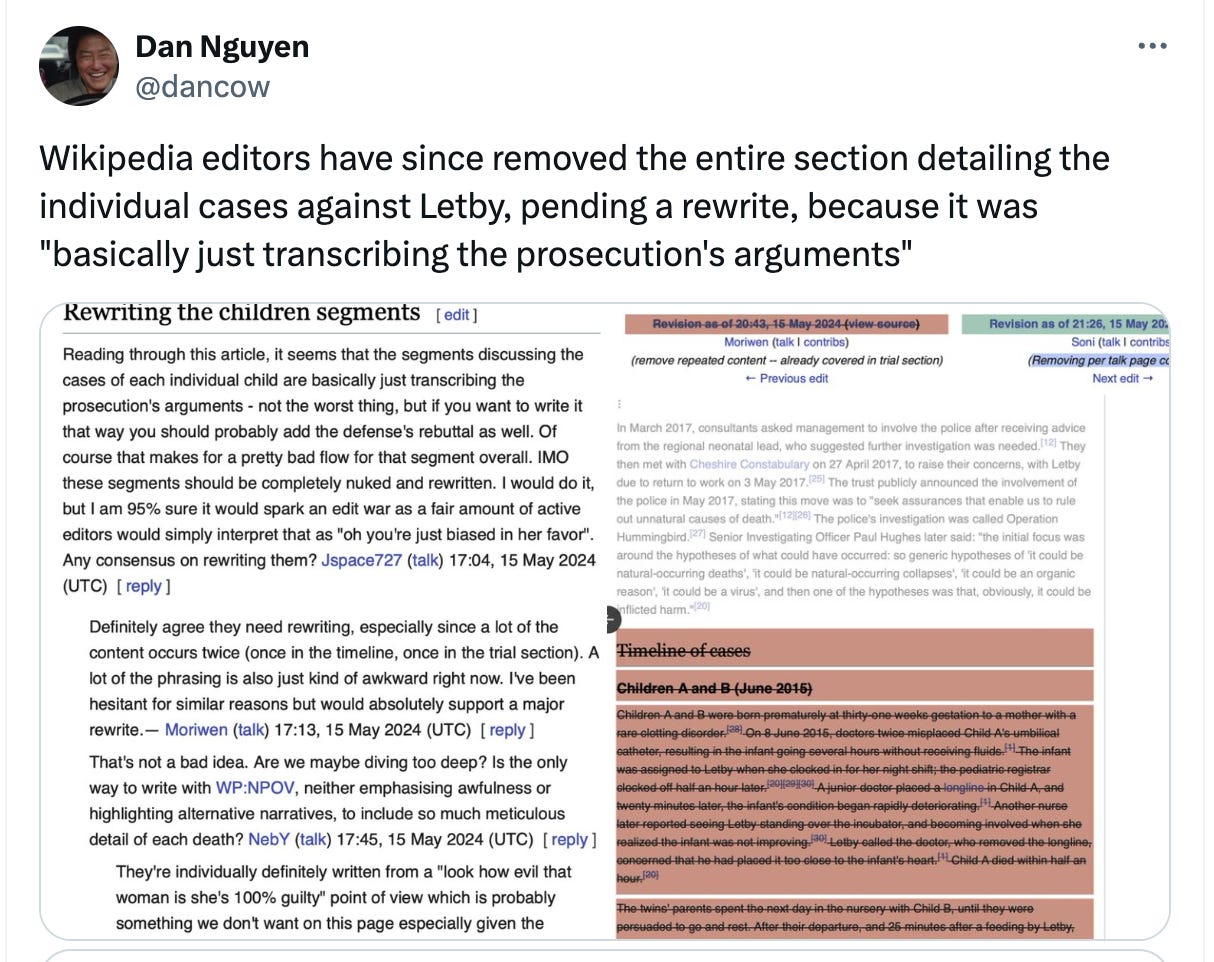

In a way, it already does, and has since 2001. Wikipedia serves this function for an enormous number of readers, and reasonably well. But reasonably well isn’t nearly good enough to inspire the kind of confidence we need on these murky, ranging, and sensitive particulars.

So what would a better Wikipedia look like?

The Problems to Be Solved

(I’m pulling here in part from a past post on the subject.)

My sense is that:

Static articles (ie. written once and then left as time capsules of evidence considered by a certain date) are a tool of a prior era, built to meet constraints that no longer exist. While high-effort investigations like The New Yorker’s are still a crucial part of the puzzle, they’re at best a partial solution.

While Wikipedia somewhat solves for this by creating a space where editors can weave together dozens or hundreds of articles into a more comprehensive picture, relying on unpaid volunteers works better for simpler cases than complex ones.

Case in point:

Shipping out articles and then leaving the public to debate them across a million different silos is not a model that lends itself well to clarification of the truth. While that public commentary is essential in itself, it needs to feed somewhere that’s both centralized and expertly curated.

What that could look like:

A Wikipedia alternative that focuses only on stories of unusual public interest

Baking in a super-powered feedback loop by giving monetary rewards to any contributor who either submits a new fact or a substantial correction

Feeding these inputs through a well-paid curation team that’s empowered with: (1) acting as journalists in consulting expert sources and filling out gaps in the evidence, (2) ensuring the output is well-structured and readable, including helpful illustrations and data visualizations, (3) spending enormous amounts of time as needed to find and work in the best arguments on both sides

Framing all this work transparently so that, to the degree that bias can’t be avoided, it’s at least explicit

This would be expensive, yes. But at a fraction of the social costs of an environment where no one knows whom or what to trust. Using napkin math, you could mock up this whole trial—including securing full transcripts—for like $250k or less. And done in a way that could reasonably represent the totality of what was presented to the jury (plus extras), all neatly indexed by major contention, gorgeously summarized for new readers, and updated forever with the best new info and counter-arguments. I can’t see how this wouldn’t be supremely valuable to readers or society more broadly.

As a useful comparison, ProPublica spent about $44m in 2023. For something like $10m, my sense is that we could produce outstanding summaries for about 40 stories a year. (There are hard limits to scaling here, where I think it’s much better to run a tighter team with a narrower scope. You don’t need to cover everything!)

But consider the value of what I’m describing as applied to contentious cases like:

The COVID lab leak theory

2020 stolen election concerns

What happened on October 7th in Israel

While I have my own personal leanings on each of those topics, the point is that a huge number of people see them as open questions. While it’s true that some folks are immovable in their perspectives, I suspect this would be meaningfully less true in a world in which these summaries really do steelman the best arguments presented by each side—without any private editorial influence on which aspects are considered important enough to cover.

Traditional journalism can’t easily produce this kind of work. It doesn’t fit their static article model, nor do they have institutional feedback loops that keep a permanently open door to rebuttals (much less any rewards for those who bring them up). Once an article has been printed, it’s exceedingly hard to get anything revisited. And while newspapers have certain thresholds for “there’s enough new information now to justify a follow-up article”, the scattering of updates between competing publications makes it hard for readers to: (1) recognize what’s actually new, (2) put it in context of what’s already known, (3) understand what counter-arguments may exist.

While forums like X and Reddit are essential for surfacing new arguments, they too have this dispersion problem. Some stories demand thoughtful centralization. And while Wikipedia was a great innovation here, it doesn't go quite far enough, and can’t itself close the gap using their volunteer model.

But there’s a better way.

For anyone curious about what this would look like, I did up this pitch a few years ago. While I couldn’t settle on the right name for it, and wasn’t in the right place to pursue it with my full attention, I still feel super strongly that it’s a missing piece of the internet that we’d all be much better off for having.

As one example here, I asked them for the DOI of a journal article that they'd referenced that I hadn't been able to find. It turns out my search problem was due to indexing on a detail (the relevant infants having been from "southeast London") that wasn't actually in said journal article. The New Yorker had reached out to the author to clarify that detail, shoring up where the article itself had been vague. (I suppose it's a bit ironic that their extra due diligence actually made it accidentally harder for me to find it. But generally I take it as a good sign when journalists put in that level of work for small details. While it doesn't necessary mean that they got all the big ones right, it's at least a positive indicator.)

She'd worked in the hospital's NNU prior, but only qualified to work on intensive care cases in 2015.

Juries in England and Wales can, with judicial discretion, convict on a 10-2 majority. In this particular case one juror dropped out during deliberations and the judge ultimately allowed for 10-1 convictions. Three counts (including one murder) were 11-0, eleven were 10-1, no verdict was reached on six (one of which is scheduled for retrial in June), and not guilty was found for two. The number of counts (22) is higher than the number of babies involved (17) as prosecutors argued that repeat murder attempts were made on several individual babies. Part of the logic for allowing majority convictions is that England has long been adverse to peremptory challenges that allow the prosecution and defense to influence jury selection. England continually reduced the number of challenges available before abolishing them outright (for most situations) in 1988, which then became official UK policy in 2007.

To Gill's credit, he's been right before, having been part of the exoneration of at least two nurses wrongly convicted in somewhat similar cases. But false negatives are a thing too. Some nurses and doctors really are killers. While I suppose I'd prefer that he argue for all potential exonerations even if a few are misguided, it seems important to bear in mind that he will sometimes be wrong (and perhaps eager in his commentary on those cases).

Baby N had been in rough shape over the night shift (which the diagram wrongly says Letby worked). Another nurse had texted Letby about this roughly an hour and half before the latter arrived for her shift around 7am. While Baby N did then have a collapse a few minutes after Letby's arrival, it's a bit sketchy to me to label it this way when the baby's condition was hardly stable prior.

Two more (the insulin cases) were added about a year later, in 2018, at least one after Letby's connection was known. While unfortunately Dr. Evans isn't currently free to clarify on the record exactly how these add-ons happened, some questions are answered in the two interviews linked.

Or at least the two numbers both seem to be 17. I’m again a bit bound here from finding out for sure given Dr. Evans’s limited ability to answer any questions on the record right now. Also, to clear up an FAQ, he said in those interviews that he’d initially received files for 32 babies. The number of incidents was higher. There are also references elsewhere (including in The New Yorker) to additional cases he reviewed later. My understanding is that these weren’t from the same time period, though it isn’t 100% clear.

Worth noting that this analysis also calls out data discrepancies between sources that would be minor in context of what this reporting normally exists to do, but that are super unhelpful in context of a murder trial. That said, it's beyond my scope or powers to adjudicate those differences here. (One dividing line seems to be whether a baby was expected to make it or not. A baby could be delivered alive but in such poor condition that survival is judged unlikely, leading to varied categorization.)

I had to stop myself from Yeah, buting the blind selection bit, since that's not your point. Your point is about steel manning and biases and I agree. Also null results aren't interesting. "Jury looked at the evidence and made the correct decision" is boring. Well researched as it may be, the Jury spent longer going over the evidence than the journalists and certainly longer than I did on podcasts, youtubes and articles. Gut still tells me they got this wrong.